Changing patterns of tourism

Although the number of overseas visitor arrivals has risen to well above its pre-Global Financial Crisis level, international guest nights are languishing at a low level. This article delves into the factors driving this divergence and assesses what effect changing international visitors’ travel patterns are having on tourism activity in New Zealand’s regions.

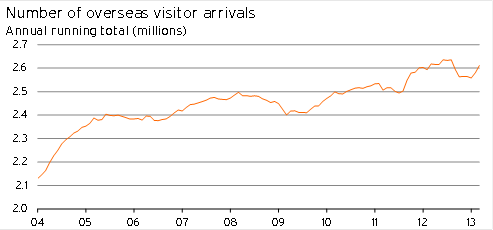

International visitor arrivals in the year to March 2013 totalled 2.61 million, a mere 0.3% less than in the March 2012 year when tourist numbers were boosted by the hosting of the Rugby World Cup. At face value, this result suggests that the New Zealand tourism industry is in a good place, but there is a lot more to current conditions than meet the eye.

Graph 5.1

The rising tide of inbound visitor arrivals is flowing from regions outside of New Zealand’s traditional sources of inbound tourism. Tourists from these new sources spend less time in New Zealand on average and follow travel patterns that are significantly different to the experiences our tourism industry has traditionally been geared towards delivering. These changes are having a profound effect on the distribution of tourist spending throughout New Zealand.

The changing face of tourism

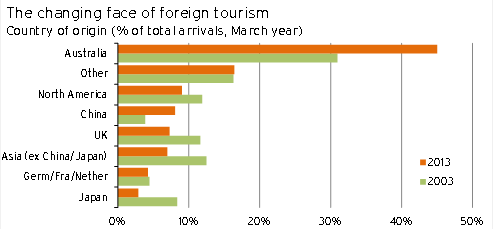

The composition of where tourists are coming from has changed significantly over the past decade. In the year to March 2003, Australia, the UK, the US, and Japan were our four most important sources of inbound tourism, representing 31%, 12%, 10%, and 8.4% respectively of total visitor arrivals. However, by March 2013, Australia’s share of visitor arrivals had risen to 45%, while the UK, the US, and Japan had fallen to 7.3%, 7.2%, and 2.9% respectively. Over the same period, China’s share of tourist arrivals grew rapidly, from 3.9% in March 2003 to 8.1% by March 2013. China is now New Zealand’s second most important source of inbound tourism.

Graph 5.2

Visitor arrivals from the US and UK have fallen significantly in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. Although financial conditions have improved over the past year, elevated unemployment in both countries and lingering concerns regarding economic stability have continued to weigh on people’s willingness to embark on expensive long-haul travel to destinations like New Zealand.

Sluggish economic growth in Japan over much of the past decade, coupled with heightened risk aversion following the Tohoku and Christchurch earthquakes, was a key contributor to the fall in visitor arrivals from Japan. Inbound tourism from South Korea has also been dragged down by risk aversion, as well as recent concerns regarding Korea’s economic outlook. Between 2003 and 2013, South Korea’s share of total tourist arrivals fell from 5.6% to 2.0%.

In contrast to these cyclical factors which have held back tourism from the UK, US, Japan, and Korea, rising visitor arrivals from Australia and China have been driven by more permanent structural factors. The increasing number of New Zealand citizens residing in Australia has led to a permanent shift in visitor arrivals from Australia for the purpose of visiting friends and family. Sharp increases in household wealth in Australia have also increased Australians’ propensity to travel for leisure, which has been met by increased air linkages between our two nations. These linkages are particularly apparent in Queenstown, where more than 85,000 visitors from Australia arrived over the year to March 2013, compared with less than 7,000 in 2003.

The remarkable rise in visitor arrivals from China can be attributed to the rapid expansion of the Chinese middle class. This newfound wealth, coupled with an easing of conditions on Chinese citizens wishing to travel abroad for leisure, has enabled an increased proportion of China’s vast population to indulge in world travel. New Zealand has captured some of this market through its reputation as a beautiful and tranquil destination, as well as through rapidly expanding business contacts and air linkages with the region. The increasing number of New Zealand residents of Chinese origin has also increased arrivals from China for the purpose of visiting friends and family.

A different type of visit

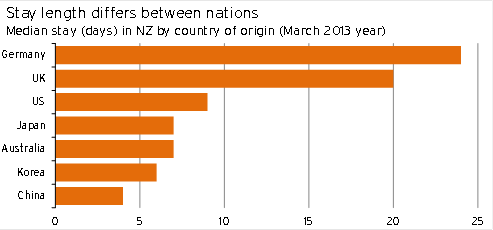

The changing composition of visitor arrivals has had a negative effect on the length of the average stay of tourists in New Zealand. In March 2004, tourists stayed in New Zealand for an average of 22 days, whereas by March 2013, the average stay length had fallen to 19 days. Looking at the median length of stay to remove the skewing effects of long-staying visitors, such as those on working holiday visas or spending a prolonged period visiting family, shows a similar story. In 2004, the median stay was ten days, whereas by 2013 it had fallen to nine days.

This pattern of falling overall stay length is best understood by dissecting length of stay by country of origin (shown in Graph 5.3). Over the past decade, there has been a significant reduction in the proportion of visitors arriving in New Zealand from longer-staying nations such as Germany, the UK, and the US. In their place, the proportion of visitors from shorter-staying nations such as Australia and China has increased significantly. Short flights and relatively low cost make quick trips worthwhile for Australians, while Chinese tourists typically visit New Zealand as part of a three or four-day add-on to an Australian holiday.

Graph 5.3

Surely this change is having an impact on spending

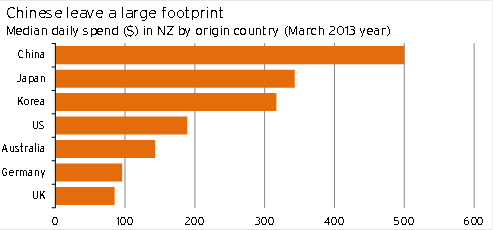

Unsurprisingly, falling stay lengths have had an effect on spending, with average expenditure per visitor falling from over $2,900 in the year to March 2004 to $2,300 by March 20131. Even with the overall lift in overseas visitor arrivals, reduced spending per visitor has seen total expenditure in New Zealand by tourists fall from $5.8bn to $5.5bn over the same period.

However, things could have been much worse. Although Chinese visitors stay for a short period of time and visit fewer places, they do leave a big footprint where they stay. Graph 5.4 shows that the median daily spend by Chinese tourists, at $500 per day, is the highest of any nation. In fact, Chinese tourists spend so much per day that their median total expenditure exceeds that of UK tourists ($2,000 versus $1,700), despite the typical UK tourist spending five times as long in New Zealand as their Chinese counterpart.

This type of extravagant spending behaviour suggests that there may be lucrative opportunities catering to the Chinese market in regions that Chinese tourists frequent. However, it is also worth noting anecdotal concerns that cronyism between Chinese tour operators and certain retail outlets, coupled with the highly structured nature of Chinese tours, means that much of this spending by Chinese tourists is likely to be highly concentrated on a small subset of enterprises in those regions. There is also a risk of measurement error in these official statistics, as the large proportion of prepayments by Chinese tourists makes it difficult to accurately separate prepayments to New Zealand firms from local Chinese booking fees and commissions.

Graph 5.4

Australian tourists spend far less extravagantly when they visit, but the sheer number of visitors from Australia means that cumulatively they provide an important source of tourist spending. Expenditure by Australian tourists over the year ended March 2013 totalled $1.6bn, compared to a total of $673m by Chinese visitors.

No time for exploring the regions

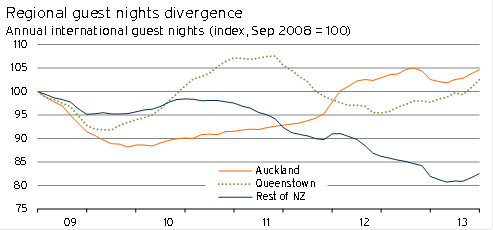

The increased prevalence of shorter-staying visitors has concentrated tourist activity on certain regions. Auckland, home to our busiest international airport, has been the biggest benefactor of this trend because almost all tourists to New Zealand spend at least a night or two in Auckland. As a result, international guest nights in Auckland have risen substantially and, by March 2013, annual guest nights by international visitors sat 4.6% above their September 2008 level (see Graph 5.5).

However, the reality is that many of these shorter-staying visitors don’t even venture out of Auckland to nearby regions. For example, annual international guest nights in Northland fell 21% between September 2008 and March 2013. Even Rotorua, which is firmly on the Chinese tour circuit, has lost out as visitors from longer-staying nations cut back. Between September 2008 and March 2013, annual international guest nights in Rotorua fell 14%. Although some Chinese tour groups overnight in Rotorua, many tours simply make the day trip from Auckland.

The Canterbury earthquakes have undoubtedly suppressed tourism in the South Island, but even so, international guest nights across much of the South Island were already weak before September 2010. Queenstown is one of the few South Island destinations to have experienced growth in international guest nights over recent years. By March 2013, annual guest nights in Queenstown by international visitors sat 2.5% above their September 2008 level. A sharp lift in the number of Australians visiting the region is behind this lift. Moreover, these figures are likely to underestimate the true rise in tourist activity in Queenstown, as a significant number of Australian tourists rent private holiday homes and apartments. This rental behaviour is not captured by the commercial guest night figures quoted in this article.

Graph 5.5

The outlook

When looking to the future of their industry, those exposed to the tourism industry need to bear in mind the two important factors which we identified earlier. The decline in arrivals from longer-staying nations is due to a prolonged trough in many developed nations’ economic cycles, while the lift in arrivals from Australia and China is more of a permanent structural shift. The risks and opportunities posed by these two factors are quite distinct and planning must take account of these differences.

The five years since the beginning of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) have been extremely trying for tourist operators in regional New Zealand who cater towards longer-staying self-guided tourists or backpackers from Europe and North America. People from these parts of the world have been reluctant to travel to expensive long-haul destinations like New Zealand when unemployment is elevated and falling house prices have led to a significant destruction of private wealth.

Although economic conditions in Europe remain weak, there are signs that conditions in the US are beginning to improve. Once European and North American economies return to a healthier condition and people become comfortable with their financial positions, there is no reason that visitor arrival numbers from these nations won’t recover to their pre-GFC levels. This recovery will take some time, given how far European and American visitor arrivals have fallen. However, at least those tourist operators who have survived over the last few years are now much leaner and more efficient than they were before the downturn and will be well poised to capture any pick-up.

Visitor arrivals from Australia will continue to be buoyed by the growing number of New Zealand citizens residing in Australia coming home to visit family. In the short-term, the prospect of slower economic growth in Australia is, ironically, another factor that may support inbound tourism from Australia. Slower growth may mean that some Australians decide to pop over to New Zealand for a quick holiday instead of a more expensive trip to Europe or the US.

The outlook for short-stay visitors from China remains good. Even if economic growth in China slows to a more moderate pace, the size of the Chinese middle class will continue to expand. This expansion will lift Chinese demand for overseas travel to places like New Zealand. Increasing numbers of Chinese New Zealanders will also boost the number of Chinese who come to visit family. However, bear in mind that these types of visitors spend a lot less than tourists who are here for leisure purposes.

A factor constraining more rapid growth in longer-stay inbound tourism from China is the visa process. At present, more than half of Chinese visitors enter New Zealand on group tours that have had visa approvals streamlined through the Approved Destination Status2 arrangement. ADS tours typically only include New Zealand as a three or four-day add-on to an Australia trip.

If visas for independent travel can be made more accessible, then the number of Chinese who visit New Zealand as their primary destination would increase and, as a result, the median stay length of Chinese visitors and the number of regions they visit would rise. Already there has been an easing of visa requirements for holders of China Southern Airline’s Gold and Silver cards, and a recently commissioned New Zealand government report has recommended that further easing be prioritised. Although this relaxation will undoubtedly help boost spending by Chinese tourists in New Zealand, some firms may struggle to gain some of this increased custom unless they tailor their product to satisfy expectations associated with the different cultural and linguistic background of Chinese tourists.

1 All expenditure figures in this article are from the International Visitor Survey which is based on a sample of departing international visitors aged 15 years and older at Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch airports. Figures exclude international airfares.

2 The ADS arrangement is an agreement with China that allows Chinese nationals to travel to New Zealand in groups for tourism purposes