Fighting inequality with minimum wage?

Raising the minimum wage

In the July quarter, the New Zealand unemployment rate fell to 5.6% – its lowest seasonally adjusted rate since March 2009. With the election just around the corner, this statistic could be seen as a boon for the incumbent National party, and a sign that they have steered us into more fortunate economic times. However, the flipside of having a lower unemployment rate, is that people may start to wonder whether we’re actually getting paid enough – hence the minimum wage debate.

Before we start, I will not deny that inequality and poverty are significant issues for New Zealand, but I will argue that if people were having an increasingly hard time finding jobs, campaigns for a higher minimum wage would more likely be replaced by campaigns for employment opportunities. Furthermore, a higher minimum wage may not be as equalising or poverty alleviating as it outwardly seems. This I will explain later in the piece.

Economic theory suggests that raising the minimum wage will lead to higher unemployment. This is because, in order for a minimum wage to work, it has to be set higher than the market wage. Theoretically, this manipulates some firms into employing less workers than they would at the market wage rate and forces workers to compete for a smaller pool of jobs, even though they would accept a lower-than-minimum wage in exchange for employment. The resulting unemployment and more expensive labour is part of the reason why countries such as Singapore have chosen not to have a minimum wage.

What is interesting about Singapore is that country doesn’t have an unemployment benefit either. In a free labour market system, theory suggests that those who do not work, do not want to work at the current wage rate. Similar to Linda Evangelista in the 90s, people will only get out of bed if the wage rate is high enough. As a result, unemployment – the idea that people are willing to work, but are unable to find work at the wage rates on offer – supposedly doesn’t exist long-term in the free market system.

By having a minimum wage in New Zealand, we as a society are saying that the free market doesn’t come up with a fair wage when left to its own devices. Instead we choose to put a lower limit on labour market prices and to offer compensation to those that are unemployed as a result of our policy (the unemployment benefit).

Research from the United States and the United Kingdom almost overwhelmingly suggests that a lift in the minimum wage has very little effect on employment. The United States Congressional Budget Office estimates that a 39% increase in the federal minimum wage (a number of states have their own, higher minimum wage rates) will result in a 0.3% percent reduction in employment. This seems small but, before we get too carried away with making numbers sound incredibly insignificant, note that 0.3% of employment in the US amounts to about half a million people. In New Zealand a 0.3% drop in employment would see 6,900 people lose their jobs.

At present, proposals for a minimum wage hike do not go quite as far as the United States’ almost 40% increase. The Labour party’s proposal for a $16 adult minimum wage would be a 12% increase, while the $18.80 ‘living wage’ would be a 31% lift from today’s minimum. These proposals will definitely have less of an effect on employment than a 40% wage hike, but will still result in a few thousand people becoming unemployed.

Having said this, perhaps now is a convenient time to lift minimum wages. If we think about the jobs that often lie at the minimum wage rate – services jobs such as hospitality, retail, and care workers –there’s an extent to how much any company can downsize. To get the same quality and quantity of work done with less human capital is limited. At a time when business is gradually picking up, employers are even less likely to downsize and are also more willing to pay higher wages in order to have access to labour.

However, raising the minimum wage has more outcomes than higher wages and a drop in employment.

It is important to consider how those who receive minimum wages and who will benefit from the increase. Information on who gets what wage is not publically available for privacy reasons but, a report by Treasury evaluates the effect of raising the minimum wage to an $18.40 ‘living wage’1 for different groups in the economy. This report shows that about two thirds of households earning between $14.25 and 18.40 per hour are those without dependants, and generally don’t receive much in the way of welfare payments. It is this group that will gain the most from the living wage.

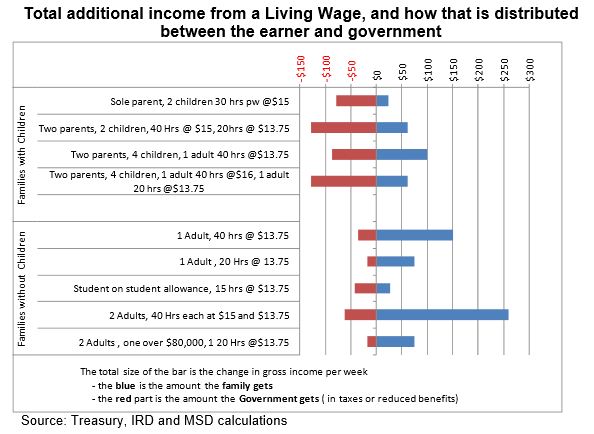

Groups that receive social assistance, particularly families, will only see a small lift in their take-home incomes under the living wage. Even though wages have increased, reduced welfare payments will offset most of the change in take home pay. In the graph below, the whole bar represents the increase in weekly income as a result of an $18.40 minimum wage. The red bar is how much of this increase ends up with the government, the blue bar is what ends up in the household’s pocket. Such a policy, funds the government first, singles without dependants second, and families last.

Even if we adjusted benefit abatements for higher low level wages, which would reduce the red bars down to just taxes, families are still at the bottom of the pile. This is because the blue bars are still smaller for those with dependents than they are for singles, making them ‘less equal’ than others. Furthermore, as everyone else’s wages and ability to buy goods increase, prices will rise. With the smaller increase in incomes to support them, families with dependants would be less able to afford these goods at these higher prices. Instead of being equalising, a lift in the minimum wage will stratify low income earners, pushing those most in need further towards the bottom.

Both inequality and poverty are significant issues in New Zealand, but simply raising the minimum wage, is not necessarily going to help solve these problems.

1 The ‘living wage’ was revised upwards to $18.80 in February 2014.