Taking on the world with free trade

Over the year to September 2014, exports accounted for 29% of New Zealand’s economic activity. As a small exporting nation, New Zealand is generally located a long way from the biggest population bases, and is trying to compete in a world where markets are biased towards domestic producers or other countries with longstanding trade arrangements. As a result, New Zealand has sought both bilateral and multilateral trade agreements as a way to crack overseas markets.

In 2014, negotiations were concluded on two landmark free trade agreements: the New Zealand-Korea Free Trade Agreement and the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA). While the former will be celebrated by most New Zealand exporters, the ChAFTA poses a threat to New Zealand’s current sweet spot in China’s domestic market. This article analyses the effects of each agreement under the timelines upon which they are set to unfold.

Furthermore, with an eye on the future and in light of the recent reboot in negotiations, this article will also look into the current status of the New Zealand- India FTA.

New Zealand-Korea Free Trade Agreement

Long-considered a catch-up agreement, free trade negotiations between New Zealand and South Korea were concluded in November 2014. South Korea has been one of our top ten export markets1 for over a decade, but New Zealand exporters face tariffs of up to 178% on our some of our major export products. With exporters from Chile, Singapore, India, ASEAN, the European Union, Peru, Turkey, Colombia, and the US all trading with South Korea under more preferential conditions, this FTA will help certain export sectors to narrow the gap between themselves and their competitors.

Pre-free trade – the current composition of New Zealand’s exports to Korea

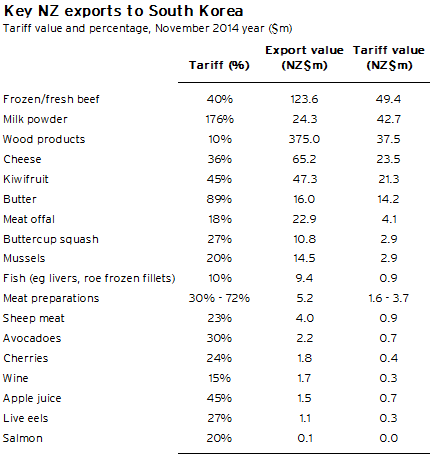

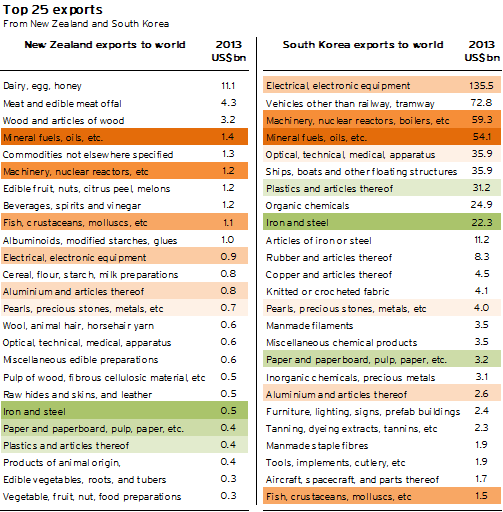

If broad export categories are used alone as an indicator, the composition of New Zealand exports to South Korea is more or less the same as that of New Zealand’s exports to the rest of the world – dominated by wood, meat, dairy, and other edibles. However, New Zealand products going into South Korea currently attract NZ$229m in import tariffs each year, with some of our biggest exports facing the highest import taxes. Table 1.1 shows the value of tariffs on some of New Zealand’s top exports to South Korea in the November 2014 year.

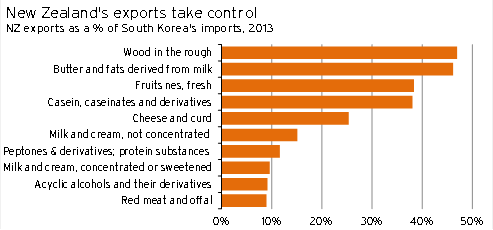

For many New Zealand exports, large tariffs place a heavy burden on the sale of New Zealand products in South Korea. Graph 1.1 illustrates the import market share of New Zealand’s tariffed and untaxed products sold in Korea in 2013. Unsurprisingly, the lack of tax on casein (a milk protein, used as a binding agent in food), has helped New Zealand to gain a 38% share of all Korea’s casein imports in 2013. At the other end of the spectrum, the 176% tariff on milk powder has heavily restricted New Zealand’s exports of milk and cream concentrates to South Korea. In 2013, New Zealand held a relatively minor 10% share of the South Korean import market for milk and cream concentrates. Over the same period, only 0.3% of New Zealand’s milk and cream concentrate exports were sent to South Korea, indicating the high capacity for New Zealand to expand milk powder exports to the country.

Table 1.1

For many New Zealand exports, large tariffs place a heavy burden on the sale of New Zealand products in South Korea. Graph 1.1 illustrates the import market share of New Zealand’s tariffed and untaxed products sold in Korea in 2013. Unsurprisingly, the lack of tax on casein (a milk protein, used as a binding agent in food), has helped New Zealand to gain a 38% share of all Korea’s casein imports in 2013. At the other end of the spectrum, the 176% tariff on milk powder has heavily restricted New Zealand’s exports of milk and cream concentrates to South Korea. In 2013, New Zealand held a relatively minor 10% share of the South Korean import market for milk and cream concentrates. Over the same period, only 0.3% of New Zealand’s milk and cream concentrate exports were sent to South Korea, indicating the high capacity for New Zealand to expand milk powder exports to the country.

In contrast, there are some exports that buck the trend and still manage to compete effectively despite hefty trade barriers. Currently facing an 89% tariff, New Zealand-made butter accounted for 46% of Korea’s butter imports in 2013. However, this market dominance is under threat given the Korea-Australia FTA that came into force in December 2014. As a result, a swift introduction of the NZ-Korea free trade agreement is necessary to ensure New Zealand competes on a more level playing field in Korean markets.

Graph 1.1

A free trade agreement with Korea won’t be the same as the NZ-China FTA

New Zealand’s relatively recent free trade agreement with China might have given us excessive optimism about the potential gains to be made from preferential trade negotiations. However, free trade with Korea is unlikely to bring about a similar boost to exports, even after making an allowance for Korea’s smaller population. Reasons why the gains are expected to be smaller are as follows.

- New Zealand was the first developed nation to have an FTA with China, which for a time provided New Zealand with a head start over its competitors. In contrast, South Korea already has preferential trade agreements with seven countries, the ASEAN region, and the European Union.

- South Korea is well-established as a developed nation, meaning that the scope for further increases in export revenue is limited by a slower growth rate in consumption. One of the core benefits to New Zealand from opening trade routes to China was the chance to capitalise on the consumption demand of a rapidly growing middle class. With Korea having a stable population of relatively wealthy consumers, the NZ-Korea agreement is likely to result in more similar outcomes to the New Zealand-Singapore Closer Economic Partnership arrangement than to China’s FTA.

- Barriers for New Zealand exporters into Korea will remain in place for longer, partly due to the heavier duties currently faced by New Zealand exporters (China had a maximum 20% tariff on NZ milk products prior to any trade agreements), but also due to the slower retreat of tariffs over time.

We’ll catch up, but not any time soon

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade estimates that there will be an immediate $65m reduction in tariff payments on exports to South Korea upon the agreement’s entry into force. But unfortunately for many of our core export commodities, it will be at least a decade before exporters are able to compete in Korean markets under duty-free conditions.

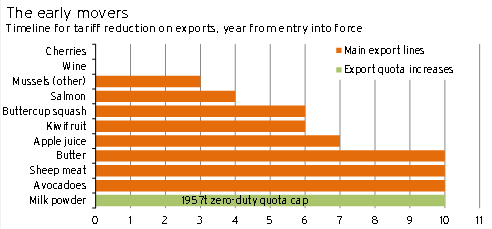

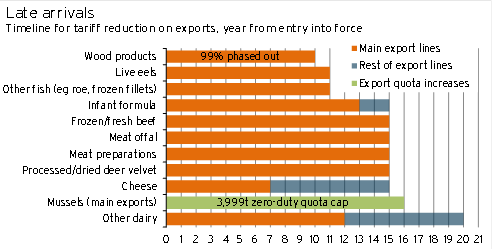

The quickest export groups to achieve duty-free status are fruit, wine, and some fish products. Cherries and wine will attain duty free status immediately, and most other fruit and vegetable categories will see tariffs completely removed within the first decade. Both South Korea and New Zealand are exporters of fish and shellfish, which has perhaps lengthened the timeline for tariff removal on particular products. Most of New Zealand’s fish and shellfish exports will become duty-free around year 11, but duty-free mussel exports will remain under a 3,999 tonne quota. Controversially, frozen squid will remain subject to a 22% tariff, despite accounting for 28% of New Zealand’s seafood exports to South Korea.

Our core export commodities of wood, dairy, and meat products will not be completely duty free until at least ten years after the agreement’s entry into force. Graph 1.2 and Graph 1.3 illustrate the phasing out timeline for key tariffed commodities.

Graph 1.2

Graph 1.3

Will a free trade agreement with Korea threaten New Zealand industries?

The difference in the mix of products that New Zealand and Korea export to the world indicates that the threat of an FTA to local industries is limited. This outcome is largely because South Korea’s main exports are goods New Zealand no longer produces, such as vehicles, or products in which New Zealand exporters occupy niche markets, such as electrical goods, plastics and machinery. Table 1.2 ranks New Zealand and Korea’s top 25 current world exports by value.

Using exports as an indicator of domestically dominated markets shows that industries in which the two countries are likely to face more competition or threats to their market share are:

- the fish, crustacean, mollusc, and invertebrate industry

- paper and paperboard producers

- some machinery groups (such as those selling fridges and freezers), as well as machinery parts makers.

Table 1.2

This increased competition forms part of the reason for delayed export liberalisation of the fish and mollusc industry – the only industry with a similar world export level that is in direct competition with South Korea.

China-Australia Free-Trade Agreement

Although our own free trade agreements play a more significant role in establishing New Zealand’s trade position with the rest of the world, it is also important to consider the agreements of our current trading partners and competitors. In November 2014, negotiations of the China-Australia free trade agreement (ChAFTA) drew to a close. With Australia under pressure to lift its export revenue – particularly through expanding its agricultural sector – will New Zealand be able to maintain its lead on dairy, wood, other consumables? This section discusses what the ChAFTA means for New Zealand – whether Australia snapped up a better deal, and whether a bigger Australian presence in China could erode New Zealand’s competitive edge.

Did the Aussies get a better deal?

Upon completing negotiations with China, Australian politicians congratulated themselves on attaining a better deal than New Zealand’s. Although the details of Australia’s “better deal” have yet to become known, what we do know from their Declaration of Intent is that Australian dairy products will be exempt from most of the protective safeguards2 that exist in New Zealand’s current agreement.

At first blush, Australia’s escape from safeguards sounds like it could be a bit embarrassing for New Zealand, but it turns out that the Aussies did us a favour. New Zealand’s 2008 FTA included a now very handy “ratchet clause”. This clause enables New Zealand to renegotiate the terms of its FTA to match any better deal signed between China and another country.

Importers have little to fear

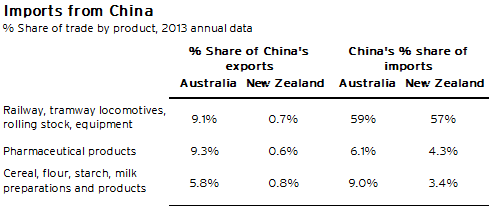

As a price taker, New Zealand has very little control over the price it pays on imports from China. As a result, a new trade agreement between a trading partner and another country can lead to price increases for the goods that New Zealand imports. However, this outcome will only occur if the new free trade partner (Australia) imports the same products as New Zealand and consumes enough of the product to influence product prices.

Of the top 100 product categories Australia imported from China in 2013, there were only three in which Australia consumed more than 5% of China’s world exports. These product groups are railway rolling stock and equipment (9.1%), cereal, flour, and starch products (which cornered 5.8% of total Chinese exports in 2013), and pharmaceutical products (9.3%). Imports from China make up 59% and 57% of Australian and New Zealand railway locomotive and rolling stock imports respectively. Tariffs on rolling stock imports into Australia currently stand at 5%. As New Zealand obtains a relatively small amount of its pharmaceuticals and cereals from China, the only area in which New Zealand is at risk of a price change is in terms of railway and rolling stock purchases. And even in this case, any price shift is likely to be relatively minor.

Table 1.3

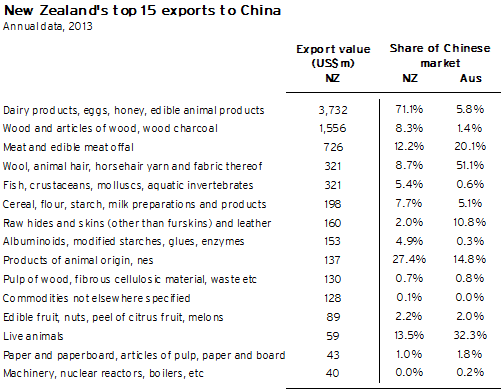

Will NZ and Australian exporters butt heads over Chinese consumers?

For the past six years, New Zealand has enjoyed increasingly advantageous trade conditions with China, but Australia’s agreement will enable our neighbour to catch up quickly. By 2019, the full 96%3 of New Zealand’s exports will be tariff free. According to a statement by Tony Abbott, more than 85% of Australian goods exports will be tariff free as soon as the Australian agreement comes into force4. Furthermore, 95% of Australian goods exports will become duty free within the following four years – bringing Australia onto a level pegging with New Zealand by 2019.

There are a number of areas where New Zealand will face more competition from Australian exports. These at-risk industries are wool, live animals, meat and offal, products of animal origin5, and raw hides, skins and leather. Australia is China’s largest source of wool products, but China already provides almost duty free access for wool, applying just a 1% tariff to imports within a 287,000 tonne quota. According to Beef and Lamb NZ, we exported 63,531 tonnes of clean wool to China and 122,071 tonnes to the world in the June 2014 year – less than half of China’s quota limit.

Both New Zealand and Australia held a high percentage of China’s live animal import market in 2013. However, a large proportion of these exports in 2013 were part of Fonterra’s plan to set up dairy farms in the region. In contrast to live cattle that are bought by foreign dairy organisations, these cows remain in a sense employed as income earners for New Zealand. Furthermore, with Fonterra operating out of Australia, New Zealand can benefit from its neighbour having better access to Chinese markets. Lastly, this export-generated expansion of Fonterra’s dairy stock in China is temporary and will come to an end when enough cattle can be bred in China itself. As a result, this export share is not likely to be threatened by Australian live animal exports.

With China rebalancing to a more consumption-led growth path and the country’s middle class expanding, Australia’s impending tariff-free access doesn’t completely undermine New Zealand’s export competitiveness. This outcome is certainly the case for protein-packed consumables such meat and dairy. In 2013, China’s total imports of meat and dairy products increased by 44% and 61% respectively from a year earlier.

Table 1.4

Talks of a New Zealand-India Free-Trade Agreement

An FTA between New Zealand and India has been under discussion since 2010, but stalled due to agricultural “sticking points” in July 2013. Interest in the agreement reignited in November 2014, with Minister of Primary Industries, Nathan Guy, scheduling a tenth round of negotiations with India’s Agriculture Minister, Radha Mohan Singh.

What was the hold up?

Trade talks reached an impasse in July 2013 with India seeking to retain protectionist measures against New Zealand’s dairy industry. India is the world’s largest producer of dairy products (by volume), but consumes most of its products internally. Based on a foundation of many small-scale farms, the industry is less efficient than New Zealand’s, leading to concern that New Zealand access could harm India’s domestic producers.

Racing against Australia again

Once again Australia is hot on our heels in trade negotiations, with Australian Trade Minister, Andrew Robb, expecting to complete negotiations for a Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement with India this year.

Could India be our next China?

In November 2013, China became New Zealand’s top goods export destination6, but this outcome was only partly due to New Zealand’s free trade access to China’s markets. The rapid rise out of poverty for many Chinese, as well as the rebalancing of China’s economic activity towards consumption-led growth, has seen China’s demand for our key export commodities explode.

Like China, India has one of the fastest-growing middle class groups in the world. In 2007, India’s middle class was estimated to be 250m people (McKinsey & Company). This group is expected to expand to 600m people within the next 15 years. According to Future Group, an Indian retailer, three quarters of India’s 2025 consumer market doesn’t even exist today. Gaining duty free access will enable New Zealand to better establish products in the Indian marketplace and be able to grow with the expanding consumer base.

Conclusion

Being heavily dependent on exports for income, FTAs have benefitted New Zealand greatly over the past three decades. However, it would be imprudent to assume that these benefits are a given with all FTAs. The New Zealand-Korea FTA, while beneficial for some exporters, does not liberate all key New Zealand exports – or at least, not very quickly. The time delay in the reduction of key export tariffs will limit the ability for New Zealand to compete against already established exporters (such as Chile and the European Union) for many years to come.

However, speculation surrounding the threat presented by Australia’s agreement with China highlights how a forward-thinking policy can help New Zealand safeguard its preferential trade relationships. The close call serves as a reminder that we must be careful when forming future agreements, and to take measures to maintain a preferential position even when new agreements are formed with our trading partners.

1 Currently ranked 5th

2 These protective safeguards are largely temporary duty-free quota limits which end in 2019, particularly on dairy exports.

3 Tariffs remain on some processed wood and paper products, as China has a previously standing agreement with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) that any preferential trade of these products must also be given to all WTO members. At the time that the NZ-China FTA came into force, these wood and paper products accounted for about 4% of New Zealand’s total exports to China.

4 Government statements suggest that the FTA is likely to come into force in the second half of 2015.

5 Mostly guts, bladders, and stomachs of animals other than fish.

6 In annual terms.