Trading doctors for cash

‘Brain drain’ is something New Zealand is inherently familiar with, particularly when those ‘brains’ cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to educate. In Cuba, thousands of students (both foreign and local) undertake fully government funded medical training. Unlike New Zealand, the Cuban government intentionally generates an oversupply of healthcare professionals, services which can then be traded for commodities, oil and foreign currency. This attempt to attain a comparative advantage in healthcare services results in an over-allocation of resources to medical training relative to domestic demand. However, the nature of this comparative advantage is fragile, as it is based on the ability of the Cuban government to retain much of the incomes its citizens earn as doctors overseas. Recent news stories have highlighted the growing trend for Cuban doctors to defect to foreign countries. Rather than forego thousands in implicit income taxes, these doctors are choosing to take advantage of richer pastures. In this time inconsistency problem, the Cuban government stands to lose millions.

Under a recent programme called mais medicos (more doctors), 5,400 Cuban doctors have been sent to fill gaps in the healthcare service in remote corners of Brazil. The mais medicos programme provides a 10,000 real (about $5,000NZ) per month salary, in addition to meals and accommodation, to each doctor in the three year programme. Of this 10,000 real, Cuban personnel receive 800 real per month in cash and 1,200 real is sent directly through the Cuban government to family at home – a way to support the economy back home and, perhaps more importantly, as means to encourage Cuban doctors to return. The Cuban government retains the remaining 8,000 real (about $4,000 NZ), effectively as an 80% income tax.

Initially in the form of aid, Cuba has practiced medical internationalism since the 1960s. Going from one doctor per 1,393 citizens in 1970 to an unprecedented one doctor per 159 people in 2005, Cuba produces enough doctors to have thousands to spare. This apparent comparative advantage has enabled Cuba to export medical services as a means to facilitate foreign policy and in exchange for much needed resources – which, since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the 1990s tightening of the US embargo, has largely been oil.

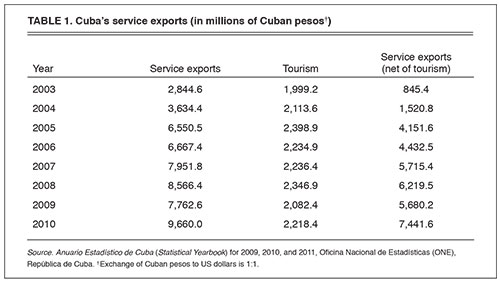

Cuban medical internationalism really kicked off in in 2003 when Venezuela agreed to provide preferential trade for Cuban exports, to partake in joint investment ventures and, not least, to provide 53,000 barrels of oil per day in exchange for a number of medical services, provisions and training. Non-tourism service exports have been the primary source of foreign currency in Cuba ever since.

The medical internationalisation scheme is an attempt at Stigliz’s “dynamic comparative advantage” – the idea that a country can create a comparative advantage by simply mass producing a resource that another country lacks. By producing healthcare services at a lower marginal cost, Cuba has coordinated its exports with the needs of others.

New Zealand also exports doctors, albeit on a far smaller scale (and with little recuperation of their foreign earned incomes) – so why don’t we just create this same competitive advantage and mass produce doctors ourselves?

Such attempts at coordination have a corresponding distortionary effect on a country’s labour market, in terms of both the choices available to people, and the choices they end up making. Although Cuban doctors are encouraged through medical training with the incentive of a higher income overseas, Cuban doctors in Cuba earn little more than a taxi driver. The fact that doctors are known to supplement their income by having side jobs in the informal economy, indicate a preference for the provision of services outside of healthcare. The existence of this informal economy, signals that the direction of funding specifically into healthcare professions is a misallocation of resources.

Secondly, In New Zealand, a six year medical degree costs our government upwards of $300,000 per person in fees alone. It is fair to assume that the cost of producing doctors would reduce should economies of scale be reached, but pumping resources into personnel for six years will come at a cost. Despite being cheaper relative to other countries, putting people through medical school en masse is an expensive exercise, one a government is unlikely to do if there is no return.

Lastly, New Zealand has few ways to ensure doctors stay under the New Zealand tax system and even if, hypothetically, we did copy Cuba’s methods, we would soon face the time inconsistency problem Cuba is now battling with. Cuba choses to solve this problem in a way New Zealand may find unethical – by restricting doctor choice and implicitly holding families as a form of security.

The Cuban government provides ‘free’ medical training and Cuban doctors generate billions in tax revenue by working for the government while overseas. Up until now, Cuba and Cuban doctors have largely cooperated (there has been but a small 2% rate of defection thus far). However, as with every time inconsistency problem there is pressure for parties to renege on their agreement for their own personal benefit.

Although the Brazilian mais medicos initiative is expected to generate $250 million US dollars per year for the Cuban government, it also poses a threat to their carefully crafted internationalisation system. Unlike previous ‘doctors-for-oil’ agreements, which were unique to the Cuban government, the mais medicos programme is open to doctors from more countries than just Cuba. Under the same contract as their Brazilian, Portuguese and Spanish counterparts, the difference between what Cuban doctors earn and what they receive is blatantly obvious. As a result, Cuban doctors are threatening to leave.

If it were easy to defect to another country, there would be a hefty incentive for school leavers to train for free in Cuba and to spend their entire practising career elsewhere. Should doctors defect to the likes of the United States, they could see their monthly incomes increase from $15-$30 dollars (at home) to upwards of $13,000. To add further pressure to Cuba’s internationalisation system, in 2006, the Unites States initiated a programme to fast track asylum for Cuban healthcare professionals working in a third country.

However, in a society where one doctor’s education is paid for by another’s taxes, it is important to realise that without the tax revenue from ‘medical internationalistas’ there is no funding for medical education (among other government funded goods and services).

Cuba provides an interesting case study in how government policies can help individuals coordinate in their choice of job and educational attainment. However, it also shows some of the costs of trying to generate a “dynamic comparative advantage”: the misallocation of human capital as people are pushed into specific areas, the restrictions to freedom required to solve the time inconsistency issue between government and the service providers, and ultimately the risk of being exposed to an industry ‘picked’ by a government.