Working with less

Following the Global Financial Crisis and Canterbury’s earthquakes, New Zealand’s capital stock per person has declined. Although we expect the amount of buildings, machines, and other capital assets per person to lift during the next five years, New Zealand’s per capita capital stock will remain below its pre-Global Financial Crisis trend.

Lost potential

In September 2012, we published an article discussing New Zealand’s “potential output” in an economic sense, and how the outlook for potential output has a big effect on how much growth New Zealand economists are expecting over the next five years.1

Here we are going to concentrate on one of the key measures that illustrates this idea: the amount of capital available. By doing so we hope to be able to articulate some of the ways that forecasts by New Zealand economists (including ourselves) are relatively conservative at present. However, we also hope to justify why we are being so conservative with our outlook for investment and the capital stock.

The capital stock has been held down since 2008 by a mixture of low investment due to the weak national and global economic situation, as well as the damage stemming from the September 2010 and February 2011 earthquakes in Canterbury.2

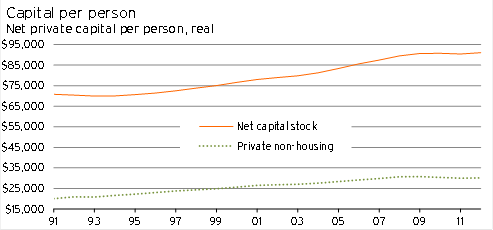

Graph 5.6

Between March 2008 and March 2012, the volume of capital per person in New Zealand rose at an average rate of 0.4%pa – well below the average 1.2%pa growth between 1991 and 2012.

Struggling to fill the gap

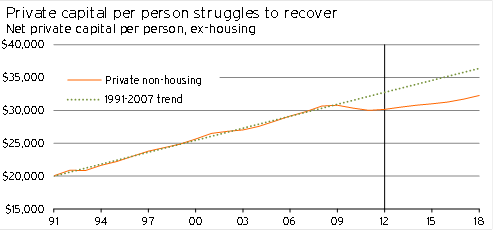

We can get a clear idea of Infometrics’ view for potential output over the medium term by comparing our outlook for private (non-housing) capital per person to the pre-Global Financial Crisis trend.

At its peak in the March 2009 year, the non-housing capital stock was worth $30,791 per person (1995/96 prices). In the following two years, capital per person dropped 2.4%. Although capital levels had recovered somewhat by March 2013, capital per person is still estimated to be 0.9% below its March 2009 level.

Graph 5.7

It is in this context that the Reserve Bank, and a number of other analysts, are stating that the “output gap” in New Zealand is near to closing up, even as per capita economic activity in New Zealand in March 2013 was still 0.9% below its March 2008 level.

We are uncomfortable going quite this far, given the technological improvements in recent years and the increasing number of favourable investment projects that will become attractive as the global economy recovers. Even so, we still don’t expect the economy return to its pre-Global Financial Crisis trend over the coming five years, and this will be represented in the capital stock staying smaller.

So why are we forecasting that private (non-housing) capital per person will remain below trend over the next five years?

· An uneven global recovery will see private investment patterns in New Zealand stay relatively restrained.

· Strong growth in residential investment and government investment, due to the rebuild, will crowd out other private investment.

· High debt levels in New Zealand will weigh upon the ability for firms to source funding for investment projects.

· Relatively restrictive lending conditions, and regulatory requirements to ensure the stability of the financial system, will limit investment.

By keeping investment and the capital stock at this lower medium-term level, we are being extremely conservative with our outlook for investment, potential output, and overall economic growth.

This conservativeness can be seen in our July 2013 forecasts for non-building investment, growing at an average of only 3.6%pa. Furthermore, the sharp lift in construction costs over the coming years (with residential building costs rising at an average of 5.9%pa between 2013 and 2018) is indicative of the crowding out we expect New Zealand to face due to capacity pressures in the construction industry, and the lift in demand for residential investment at the expense of other forms of investment.

However, in the long term these types of gaps in the capital stock are almost always closed up, as resources are shifted into their best use and patterns of technology make prior investment obsolete. Once this process takes hold investment, and potential economic growth, will pick up significantly. As a result, beyond our forecast horizon, we expect capital investment to return to its long-term trend.

It is possible that this adjustment will occur more quickly than we have allowed for, especially if the legacy of high New Zealand debt levels is less binding, in terms of investment choices, than we are currently assuming.

Conclusion

New Zealanders are currently “working with less” capital than they were before the Global Financial Crisis took root. In this environment, it will be more difficult for the country as a whole to ramp up output (GDP) without going on an investment spending binge.

The Canterbury rebuild and Auckland Housing Accord will ensure that investment in New Zealand is concentrated in “non-tradable” areas for the coming years, crowding out other forms of investment. Combined with financial markets that are still scarred from the GFC, this outcome implies that the stock of private capital (excluding residential building) will remain below its pre-recession trend.

With relatively less capital to use, relative to trend, economic activity will also stay below the pre-crisis trend in the medium term.

1 infometrics.co.nz/Forecasting/6091/901/Investigating-New-Zealand%27s-potential

2 The March 2012 capital stock figures from Statistics NZ, which we are using here, include early estimates for the cost of the Canterbury earthquakes. If anything, the capital stock figures from 2011/12 are likely to be revised down further in the coming years.