Why is Fonterra losing grip of market share in the dairy industry?

Fonterra’s share of the New Zealand dairy market has fallen substantially over recent years, driven down by a rapidly expanding competitive fringe of smaller export-orientated dairy firms. This article examines how the industrial structure of the New Zealand dairy industry has evolved over the past decade and identifies reasons why changes have occurred.

The New Zealand dairy industry was deregulated during 2001, with the goal of boosting New Zealand’s competitiveness in world dairy markets. Following deregulation, nearly all dairy cooperatives merged to become Fonterra in October 2001, and export restrictions were gradually removed. The only two dairy cooperatives to remain independent were Westland Milk Products on the West Coast and Tatua Cooperative Dairy Company in Morrinsville, Waikato.

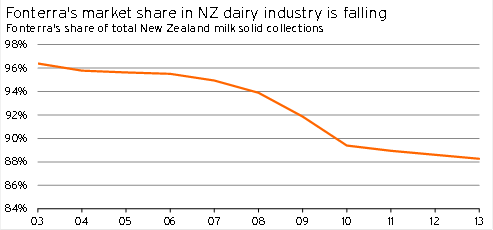

In the first full dairy season following Fonterra’s creation, the company collected 96% of New Zealand’s total milk production. But over the intervening years, Fonterra’s market share has steadily declined (see Graph 1.1). By the 2013 dairy season, Fonterra’s share had fallen to 88%, and over the first six months of the 2014 season, this share had slipped further to 87%.

Graph 1.1

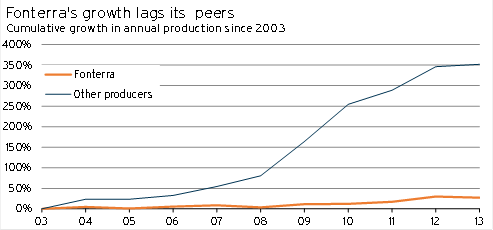

Although Fonterra’s falling market share may seem ominous at first glance, things are not as bad for the cooperative as they appear. Fonterra is not in absolute decline, it is just that the company is growing at a far slower rate than its competitors.

Between the 2003 and 2013 seasons, the quantity of milk collected by Fonterra’s competitors increased four and a half fold, with Fonterra’s total milksolid collections rising a more sedate 27% over the same period. Graph 1.2 puts these vastly different growth rates in perspective. With milk collections by small firms growing so rapidly, it is easy to see how their share of the New Zealand dairy industry has increased from 3.6% to 13% over the past decade.

Graph 1.2

The competitive fringe

Before discussing what has driven such rapid growth among small dairy companies in New Zealand, let’s take a moment to understand the structure of this competitive fringe in the dairy industry.

As outlined earlier, the only two cooperatives to remain independent of Fonterra in 2001 were Westland and Tatua. However, in the years that have followed, a number of other small dairy companies have entered the New Zealand market. In 2006, Westland and Tatua still accounted for 94% of milk supply outside of Fonterra, but by the 2013 season, these two cooperatives only accounted for around 35% of residual production.

Key entrants to the New Zealand dairy market have been Synlait, with a factory in Rakaia (Canterbury), and Open Country, with production facilities in Wanganui, Waharoa (Waikato), and Awarua (Southland). Both of these producers are non-cooperative dairy companies.

Since beginning production in 2004, Open Country has grown swiftly to become New Zealand’s second largest dairy processor, ahead of Westland Milk Products, which has been relegated to third position. Rapidly growing Synlait, which began producing in 2008, is the fourth largest processor.

Another start-up to enter the market was Miraka, which swung into production in August 2011. Miraka has a factory based in Mokai, north of Taupo, and is owned by a consortium of Maori trusts along with a Vietnamese dairy company and the Global Dairy Network. Detail of milk collections by Miraka are scant but, based on the processing capacity of the factory and the number of cows supplying the company, we estimate that Miraka collects just under half the milk that Synlait does. Miraka will grow quickly over the coming years as it commissions a new UHT plant.

The smallest dairy company occupying the competitive fringe is Tatua Cooperative, which in the 2013 season collected around 0.8% of New Zealand’s milk supply.

The six companies listed above are the only significant going concerns that currently collect milk from farm suppliers. However, there was an unsuccessful direct investment by Russians in 2007 into a greenfield production facility in Studholme, Canterbury. The Russian-controlled company, NZ Dairies Ltd, eventually went bankrupt, and the factory was purchased by Fonterra in 2012.

Over the coming year, Oceania Dairy Ltd, a subsidiary of Chinese company Inner Mongolia Yili Group, will also enter the market. Oceania Dairy expects to commission a new factory in Glenavy, Canterbury, by mid-year, in time to start collecting milk from farmers in the 2014/15 season. The company’s production projections suggest that, by 2017, Oceania Dairy could be collecting around 300m litres of milk (equivalent to around 1.5% of New Zealand’s current milk supply). Based on this projection, Oceania Dairy would nestle in between Miraka and Synlait in terms of size.

Another new Chinese entrant, Yashili, has also recently begun construction of a new factory in Pokeno, south of Auckland. The new dairy factory will produce infant formula for the Chinese market and is expected to be operational by February 2015. The Pokeno facility will be slightly bigger than Oceania Dairy’s factory, with a production capacity of 52,000 tonnes per annum of finished product compared to Oceania Dairy’s 47,000 tonnes capacity. These figures compare to Synlait’s 2013 production of just under 92,000 tonnes of finished products.

There are also other new dairy factory projects at various stages of development being currently mooted by new entrants. For example, a small ($100m) plant has been proposed by Dairyland Products for a site in Tokoroa. The company intends to begin construction this year, so long as it raises the necessary capital to finance the project.

Other proposed projects are less certain, including a factory in Apanuni, South Waikato and one in McNab, near Gore in Southland. The company behind the Arapuni project, Arapuni Milk, has already gained consent for using the site for dairy factory use, but outside of this detail the trail has gone cold. The Southland site is being pushed by Mataura Valley Milk, but has thus far been unable to raise the necessary capital to get the project off the ground.

Why have smaller dairy firms grown so rapidly?

With the size of the competitive fringe of smaller dairy firms and the number of firms comprising this group having risen so swiftly over the past decade, it is important to ask ourselves what has enabled such rapid growth. To solve this problem, we must consider:

- why investors have been willing to bankroll substantial investment into new production facilities, and

- why dairy farmers are choosing to supply these smaller processors instead of sticking with Fonterra.

What has driven investment?

The key motivator behind an investor’s decision to put their cash into constructing a new dairy production facility is an expectation that the operation will yield an adequate risk-adjusted return on their initial investment. In other words, the investor is usually motivated by the potential for future profits.

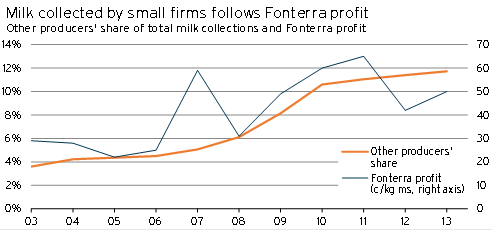

Over the past decade, Fonterra has been able to consistently raise its profit levels per kilogram of milksolids collected (see Graph 1.3). This trend didn’t go unnoticed among other potential dairy producers, who took Fonterra’s rising profit margins as a positive sign of profit-generating capacity in the industry and formed expectations that they too could replicate this success. The investing community also took note, and these small dairy companies have been able to successfully raise capital for investment into new dairy production facilities.

Graph 1.3

However, not all small dairy companies have been able to replicate the profitability of Fonterra1. For example, in 2013, Fonterra generated about 50c of profit per kilogram of milksolids, while Westland and Synlait generated a mere 23c/kgms and 27c/kgms respectively.

A factor constraining some smaller dairy companies’ profitability is that they are forced to pay a higher farmgate milk price than Fonterra in order to capture suppliers. At the same time, these companies produce a similar product mix to Fonterra which, in turn, is priced more or less comparably in export markets.

Given that investment in production facilities by small companies shows no signs of waning, despite apparently lower profit margins for some companies, we can conclude two things.

- Either these small dairy companies are still in a growth phase and will become more profitable in the future, or

- shareholders of these small companies perceive this lower return on their investment as being adequate.

The first of these conclusions is reasonable given that many of New Zealand’s small dairy companies have only been operating for a few seasons and firms typically become more profitable as they mature. This increasing profitability over time is precisely what has happened to Fonterra as the company has matured (see Graph 1.3).

Profitability can also increase over time as product mixes change. For example, Tatua generated a healthy 83c/kgms of profit during 2013 (as well as paying a higher implied farmgate milk price to suppliers than its competitors did). The key driver of Tatua’s relatively high profitability is that Tatua’s product mix is geared towards supplying higher-end processed consumer and food service items, rather than its competitors’ simpler array of lower value-add products like milk powder and butter.

The second conclusion above implies that, if investors really are willing to accept lower returns, then it follows that Fonterra has historically generated an excess return for its farmer shareholders. This suggestion is not inconsistent with the events that followed the listing of the Fonterra Shareholders Fund on the New Zealand stock exchange in November 2012. Fonterra sold units in the fund during the IPO process at $5.50/unit, but on listing day the units soared as much as 22%. Such a price premium shows that investors were willing to accept much lower dividend yields than had been anticipated by Fonterra2.

In the case of dairy companies with shareholder suppliers, the lower profit margins may also be acceptable if they are accompanied with correspondingly higher farmgate milk prices. This scenario reflects what happened in 2013 for shareholder suppliers to Westland, who received $6.34/kgms in total for farmgate milk prices and their share of production profits. This total return was exactly in line with the same metric for Fonterra shareholder suppliers. As a result, the production profitability differences could be explained by the two companies choosing to divide their returns between the two parts of the supply chain differently.

A final reason for investing in dairy production in New Zealand is to ensure security of supply. For example, this motivation is likely to be a factor behind China’s largest dairy company’s decision to invest in a production facility in Glenavy. If foreign companies do invest to shore up the security of supply, then they may be willing to pay farmers a premium to guarantee the reliability of milk supply, even if this milk price premium comes at the cost of production profits.

Why would farmers switch dairy companies?

With regards to farmers’ willingness to begin supplying these small companies, at first brush, the simple reason for this choice would appear to be higher farmgate milk prices. Without exception, small dairy companies consistently pay farmers more for their milk at the gate than Fonterra does. However, there are also other reasons behind the decisions of farmers than initially meet the eye.

In the case of cooperatives, where farmer suppliers are also forced to be shareholders in the company, farmers may look past lower total returns because they value having a voice in a smaller local enterprise. It is also possible that shareholder suppliers believe the cooperative will become more profitable in the future (eg. replicate Tatua’s success)3.

In the case of farmers that supply non-cooperative dairy companies, but don’t hold shares in the company, the farmers could value the financial freedom this decision brings them. These farmers can have the best of both worlds – they can receive a higher milk price than Fonterra would have paid them and have the added advantage of not having to tie up additional capital investing in the milk production side of the dairy industry. As a result, these farmers are better able to diversify their wealth into different investment classes and industries than if they had been a shareholder supplier.

How can understanding the dairy industry’s industrial structure help us?

Given the above discussion, it should now be clear how the dairy industry’s industrial structure has evolved, but it is also important to understand what makes the dynamics of the industry relevant from a broader economic and business perspective.

If a dairy company chooses to invest in a new factory, there are significant implications for the local region’s economy. The injection of capital into the region during the construction phase helps boost a region’s building industry and associated support services. Then once the factory is operating, there is also the creation of employment at the factory, as well as some additional demand for businesses contracted to provide services to the company. For small local businesses, it may be easier to get their foot in the door supplying a smaller dairy company in their region, rather than a larger enterprise with centralised procurement for operations nationally.

The entrance of a new dairy company to a region could also push up the price of existing and potential dairy land in the area. If the new dairy company can be reasonably expected to consistently provide a larger payout to farmers than Fonterra, then these increased returns should be capitalised into higher farm prices. If these higher profit expectations are not capitalised into land prices, then the implication is that there is a very high risk premium associated with the new factory.

Finally, in addition to these economic and financial considerations, understanding the gradual erosion of Fonterra’s market share also enables us to better interpret partial indicators of milk production. We can use Fonterra’s milk production data to get an early idea of how the current production season is unfolding for dairy farmers nationwide. At present, complete monthly data of total New Zealand milk production is only available with a lag of about six weeks from the Dairy Companies Association of New Zealand (DCANZ). However, data regarding Fonterra’s production level is available in a timelier manner, with its Global Dairy Update published approximately two weeks after the end of the month in question.

Even though Fonterra is losing market share to its smaller competitors, the company still controls 87% of national milk collections, so trends in Fonterra’s milk collections still broadly reflect what’s happening to the New Zealand milk supply. When interpreting Fonterra’s data, we simply have to bear in mind that it will be an underestimate of total milk production growth in New Zealand. For example, for the current milk season until November, Fonterra’s milksolid collections were 3.8% above their level from a year earlier, whereas total New Zealand milksolids production rose by 5.5% over the same period – a divergence explained by the rapid 20% growth in milk collections by smaller companies. Understanding the nature of this divergence allows us to more effectively put partial production data from Fonterra into perspective, thereby more quickly coming to grips with current conditions for the dairy industry.

1 A precise decomposition of the profitability of Open Country and Miraka was not available due to the two companies being privately held.

2 The price of Fonterra Shareholders Fund units has recently settled just below $6/unit. However, this change is in response to recent downgrades of underlying dividend payment expectations, on the back of lower profitability this season, rather than an increase in the implicit required yield by shareholders.

3 This latter reason could also be true for shareholder suppliers in non-cooperative dairy companies.