Developing risks from the developing world

Although a sharp rebound in growth in New Zealand looks assured, one significant downside risk remains – a sizable slowdown in Asia. In this article we discuss some of the capital market pressures in Asia over recent months, what could go wrong, and why we don’t think events in Asia will derail growth in New Zealand.

Our forecasts paint a rosy picture of the next couple of years, with rising global and domestic demand driving a sharp lift in economic activity. However, there is one downside risk to this recovery that overshadows all others – the fragility of emerging markets.

These risks came to the fore in January, as capital outflows from emerging markets picked up. Here we will summarise what has happened, the risks, and our current view.

What about the tapering of quantitative easing in the US and UK?

Ultimately, the risks around emerging markets are heavily tied to the tapering going on in the US (and to a lesser extent the UK). However, it is not the tapering that is directly a threat to the economic recovery, but the effect it may have on already-fragile emerging markets.

The direct effect of tapering on New Zealand is as follows.

- Tapering will reduce demand for high-risk assets, such as the New Zealand dollar. The value of the New Zealand dollar will decline in the near term, especially against the US dollar.

- By implicitly tightening credit conditions overseas, and by pushing down the value of the New Zealand dollar, tapering will lead to higher interest rates or tighter credit conditions than would have been the case in the absence of tapering.

As a result, the net effect of tapering will be to change the relative nature of the recovery (improving returns to exporters and reducing activity by those who have borrowed), but tapering will not undermine the recovery.

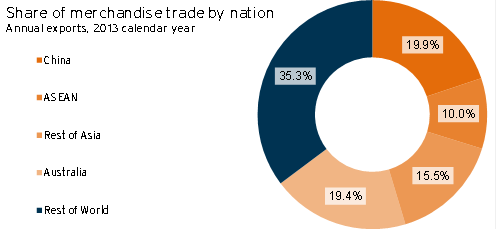

Graph 5.25

Instead it is the indirect effect, through New Zealand’s trade with Asia, which is the key concern. We will explain the focus on Asia below when we discuss exactly what is going on with tapering. However, it also pays to take a look at our current export exposure to Asia – this exposure is shown in Graph 5.25.

What is going on in emerging markets?

It is important to separate current trends in emerging markets into two categories – the economies that are imploding based on their own recent choices, and the economies that may be experiencing trouble due to tapering.

Where tapering is not the main concern

As the persistence of tapering became clear, four countries experienced the strongest capital outflows and sharpest depreciations in their currencies in late-January: Argentina, Russia, South Africa, and Turkey. The turnaround in capital flows for those countries was so strong that some analysts started calling on the Fed to stop tapering.

However, apart from possibly South Africa, these nations were experiencing such a sharp response because of what was going on domestically at the time. Argentinean monetary authorities have lost control of the currency after a long period of populist political policies that were funded by implicit inflation. The Turkish government is looking more and more like a dictatorship by the day, and a fragile one at that. Furthermore, a combination of domestic weakness and collateral damage from events in Ukraine have led to sizable capital outflows from Russia.

Although South Africa did not have a specific event that caused the outflow, the combination of persistent labour strikes and a fragile economy had made South Africa a country where investors were already on record about fearing capital flight – making a small run on the country become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The size of the capital outflows in these countries appears scary, but the outflows are largely unrelated to tapering. As a result, analysts that discuss tapering by focusing on these nations are often exaggerating the effect of actions by the US.

The countries responding to tapering

Even when we look at the countries experiencing volatility from tapering, it is useful to separate these countries into two groups: countries experiencing capital outflow due to tapering and those that aren’t.

When tapering first started, India experienced a sharp depreciation in its currency and an outflow of capital. However, when the highly regarded Raghuram Rajan was brought on board as the head of India’s central bank, his actions managed to stabilise the currency.

The more recent round of concern about tapering in late January led to a sizable drop in the Indian rupee, but also the Thai baht, the Malaysian ringgit, the Vietnamese dong, and Philippine peso. It was surprising that the Thai baht did not struggle more, given the domestic political uncertainty that has been unfolding in the country.

As Dani Rodrik recently pointed out1, it isn’t the fault of the US and the UK that these countries are now struggling to deal with tapering. The policy was announced early, and the direction of its effects was known. The developing countries could have lifted interest rates or preferably limited capital inflows to deal with the fact their financial systems were not mature enough to cope with the increase in risk-taking from international investors.

On the other side, China is the key example of a country not experiencing capital outflows due to tapering. China’s massive reserves, especially of US government bonds, combined with strong domestic investment, imply that there was never much scope for quantitative easing and tapering to have much of a direct effect on capital flows into or out of China. In fact, capital inflows into China have strengthened in recent months.

Nevertheless, China is undeniably feeling the heat. A mixture of domestic policies focused on increasing consumption and a slowdown among countries involved in China’s supply chain has conspired to drive the Chinese performance of manufacturing index down to its weakest level since mid-2013, when the concerns about tapering first escalated in Asia.

At present, there is a lot of rhetoric stating that matters are just going to get worse for China. However, it is important to note that the drop-off in manufacturing activity in China in mid-2013 was only temporary. Furthermore, in January, the US (China’s biggest export market) had just experienced a major snowstorm that had seen domestic demand weaken sharply. It will be a few months until it is clear whether the recent slowdown in China is a flash in the pan or is something more sinister.

What is a possible negative scenario?

As we have written previously, when thinking about trade with Asia it makes more sense to think of the region as an integrated supply chain – rather than looking at countries by themselves.

In this context, the sudden exchange rate and economic volatility among Asian countries is likely to affect trade activity. We are already seeing a sizable effect on growth in the Australian economy due to reduced demand for hard commodities.

If matters turn for the worse, there are a number of indicators we would expect to see.

- If underlying production in Asia fell to the extent that it squeezed middle-class incomes, there would be a corresponding drop in demand for commodities. As a result, New Zealand’s export commodity prices would decline.

- The first place we would see this effect coming through would be the exchange rate. With demand for trade goods falling, the New Zealand dollar would start to depreciate against most of our trading partners. However, given the nature of the slowdown, the AUD/NZD cross-rate would be unlikely to fall, as this outcome is still bad for the Australian economy.

- The Chinese shadow banking system has grown significantly in the last six years, and has been used to largely fund residential developments and local government infrastructure projects. In a worst-case scenario where the prices of New Zealand commodities are falling sharply, it is likely we would also be facing a bank run in the Chinese shadow banking system – the same type of event that the US and Europe faced following the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the bankruptcy of AIG.

We would currently place a 5% probability on such a scenario – so out of every 20 such events, we would envisage matters going south this way only once.

Even in this scenario, the fallout for the New Zealand economy would not be as bad as the Global Financial Crisis. The US economic recovery would be sufficiently self-sustaining to avoid a global crisis, while the Canterbury rebuild and relatively good access to credit would help to boost domestic investment.

Nevertheless, there would be a significant adjustment in New Zealand’s terms of trade. Fonterra and other commodity sellers would be forced to find other markets for produce, selling in some cases below cost. This negative income shock would see a drop-off in consumption spending and a sharp pull-back in bank lending to the agricultural sector.

In a nightmare scenario, we could envisage large-scale defaults on agricultural debt, a sharp adjustment in house prices, and a seizing up in lending in both Australia and New Zealand, putting the Australasian banking system at risk. However, this extreme outcome is very unlikely.

What do we expect?

Tapering is interrupting the Asian supply chain, and having a negative effect on the Australian economy. However, unlike the negative scenario outlined above, we do not expect the breakdown in trade co-ordination and financial conditions in Asia to deteriorate enough to have a significant negative effect on New Zealand’s commodity export prices.

Unlike Australia, New Zealand is not pinned directly to the outlook for production in “Factory Asia”. Instead, New Zealand sells products more directly to the middle classes in Asia – both in terms of food (dairy products, meat) and construction materials for residential property (forestry products).