Assessing the effect of lower milk prices on regional dairy payouts

The sharp decline in dairy prices since their February peak will have a significant effect on farmers’ incomes and their willingness to spend and invest this dairy season. This article examines what potential farmgate milk price scenarios mean for each territorial authority’s dairy payout.

After peaking in February, milk prices at Fonterra’s GlobalDairyTrade forward auctions have declined close to 50%. Fonterra’s current payout forecast for the 2014/15 dairy season is $5.30/kgms (down from $8.40/kgms last season), but there are downside risks to this payout. These risks stem from Fonterra’s assumption that milk prices at GlobalDairyTrade auctions will recover 30% by March 2015.

Lower dairy prices have been driven by Chinese dairy demand being partly met by temporarily running down milk powder stocks in China at a time when soaring milk production volumes in Europe and the US are rapidly adding to the global dairy supply. We will revisit these factors again later in the article, but for now let’s focus primarily on what different farmgate milk price scenarios for the current season will mean for the dairy payout in each territorial authority in New Zealand. This information, taken in conjunction with the size of each territorial authority’s dairy farming sector relative to GDP, can help assess the short-term risks posed to the district’s overall economic health.

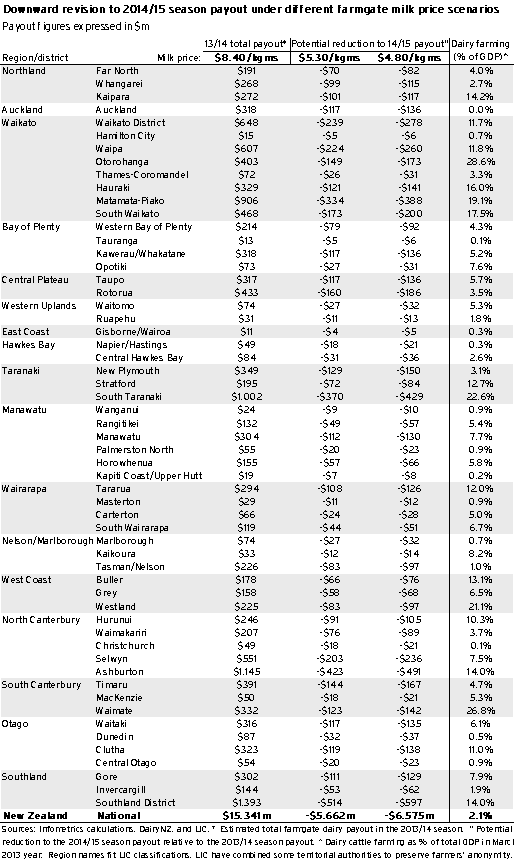

At a New Zealand level, we estimate that a farmgate milk price of $5.30/kgms in the 2014/15 season would represent a $5.7bn reduction to the total dairy payout compared to the 2013/14 season1. And if the milk price ends up falling a further 50c to $4.80/kgms, then the total payout would be $6.6bn lower than last season’s payout.

Table 1.1 decomposes the effect of these two potential milk price scenarios for the 2014/15 season on the dairy payout for each territorial authority. The table shows how much the payout would decline under each scenario compared to our estimate of the TA’s 2013/14 season payout, and also presents the size of the dairy cattle farming sector as a percentage of each district’s local economy.

Although at a national level the sharply lower dairy payout will do little more than take the shine off buoyant production and demand in many other sectors, the same cannot be said for districts that are heavily reliant on the dairy sector. Data shows that the New Zealand economy’s direct exposure to dairy cattle farming is just over 2% of GDP, but there are some districts (mainly in Waikato, Taranaki, and the South Island) where this exposure is well above 10% of GDP (and even above 20% of GDP in some cases).

In these highly exposed districts, the lower dairy payout will not only reduce farmers’ incomes, but there will also be significantly slower growth in activity in other parts of these local economies. This flow on effect will be caused by dairy farmers and their contractors showing a reluctance to spend and invest on anything but the necessities.

Table 1.1

Our estimates show that North Island dairy farmers look set to take a $3.3bn-3.8bn hit to their incomes this dairy season. These reduced incomes will be felt most keenly throughout Waikato and Taranaki, as dairy farming is the biggest contributor to economic activity in the Waikato District, Waipa, Otorohanga, Hauraki, Matamata-Piako, South Waikato, Stratford, and South Taranaki economies. The collective $1.3bn-1.5bn hit to dairy farmers’ incomes in Waikato and $570m-660m decline in Taranaki farmers’ incomes are likely to see a significant scaling back of spending and investment intentions in these regions.

The rest of the North Island is generally not as highly exposed to dairying as vast swaths of the Waikato and Taranaki regions, but Table 1.1 does still identify pockets of risk in districts such as Kaipara and Tararua. Some business owners in parts of Bay of Plenty, Manawatu, and Wairarapa will also face more difficult trading conditions over the coming months, as these regions have moderate exposure to dairy farming.

We estimate that South Island dairy farmers will face a $2.4bn-2.8bn decline in their incomes this dairy season compared with last season. These lower payouts will hit the Southland and West Coast economies particularly hard, as well as parts of provincial Otago and Canterbury that are highly exposed to the dairy sector.

The outlook for dairy prices

Having identified the magnitude of declines to dairy payouts in each district this season, we will now briefly turn to understanding some of the issues pertaining to the outlook for dairy prices. After all, the severity of the actual pull-back in spending and investment activity by dairy farmers over the current dairy season will depend on whether they expect their incomes to be temporarily or permanently lower.

A temporary hit to incomes will have little effect on spending as it can easily be smoothed out by drawing on short-term credit facilities. However, permanently lower dairy returns would cause a rethink of underlying operating practices and production capacity for some farmers.

As with all markets, global dairy prices are the outcome of both supply and demand factors. Unfortunately for New Zealand, both of these factors are pushing in the “wrong” direction at present. Not only has global demand for traded dairy products shown some softness over recent months, but supply from other key dairy-producing nations is picking up strongly.

Two factors have contained global demand for dairy products of late:

- China meeting some of its dairy demand by running down accumulated stockpiles of whole milk powder, and;

- Russia’s retaliatory ban on dairy imports from Western nations in response to Western sanctions on Russian businesses.

Luckily for farmers, these two factors are temporary and will eventually cease to be a limiting factor on global dairy demand. Of the two, we would expect Chinese dairy imports to pick up first as milk powder stockpiles have a finite size, and anecdotal evidence suggests that Chinese dairy buyers will return to the market later in the year. The timing of Russia lifting its boycott is more difficult to predict as it will depend on geopolitical factors. Once these two issues are resolved, we expect ongoing growth in demand for protein in emerging nations to continue pushing up global dairy demand over the medium-term.

However, supply-side driven weakness to global dairy prices is of greater concern. The key lifts in supply from other dairy-producing nations at present are coming from Europe and the US. Milk production in the European Union rose by 5.0% in the six months to June from a year earlier, while production in the US over the three months to August was up 3.0% from a year earlier. To put the magnitude of these increases in perspective, a 5.0% lift in Europe’s annual production is equivalent to around one-third of New Zealand’s annual milk production, while a 3.0% boost in annual US milk production is equivalent to around 12% of New Zealand’s total annual milk production.

Although the pace of this supply growth is likely to moderate over the coming year in response to sharply lower dairy prices, Northern Hemisphere dairy producers still pose a significant competitive threat over the medium-term, particularly when one factors in the upcoming abolition of milk quotas in Europe in April 2015. This policy shift will support both a permanent structural lift in the level of European milk production and a concentration of this production in the parts of Europe that produce milk most efficiently.

To counter this competition, New Zealand dairy farmers’ must ensure that they keep a tight rein on milk production costs. Traditionally New Zealand’s pastoral dairy farming system has enjoyed a significant cost advantage over the barn and feedstock system used in Europe and the US, but this advantage has eroded significantly over recent years. Data from the International Farm Comparison Network even shows that some of the most efficient large dairy farms in California now enjoy lower production expenses than some of the higher-cost producers in New Zealand.

After weighing up all of these factors, we assess that risks to Fonterra’s farmgate milk price forecast of $5.30/kgms for the current dairy season are skewed to the downside. Although we expect a gradual lifting of demand-side constraints to support some stabilisation of dairy prices moving into 2015 and beyond, we anticipate that ongoing strength in global dairy supply will remain a limiting factor that prevents global dairy prices from returning to their lofty heights of the 2013/14 season anytime soon. In this environment, dairy farmers are likely to be relatively conservative with their spending patterns, which could see some rural contractors and merchants in regional New Zealand face leaner trading conditions over the coming season or two.

1 For simplicity, payout calculations have been based on the assumption that milk production in the 2014/15 season is equal to 2013/14 production levels. This simplification allows for an easier subnational decomposition and does not materially affect overall conclusions regarding the change in the payout, as the magnitude of the decline in milk prices dominates any marginal increases to milk production in calculations.