Taking stock of Europe’s recovery

This article takes a look at how the European economic recovery is progressing. Although only a small proportion of New Zealand’s exports head directly to Europe, the state of economic conditions and demand in Europe can still have significant effects on commodity prices. Furthermore, Europe’s stabilisation is good news for New Zealand banks, as it will help keep international financing conditions for our banks favourable.

European markets breathed a collective sigh of relief in the middle of 2013 when official data confirmed that the euro area had officially climbed out of recession in the June quarter. Having contracted for six consecutive quarters, economic activity in the euro area rose by a seasonally adjusted 0.3% in the June quarter. This lift was driven primarily by France and Germany. Economic activity in Germany was particularly strong throughout the middle of the year, which saw Germany’s unemployment rate fall to its lowest level since reunification between East and West Germany.

Nevertheless, embattled euro-area members Italy and Spain remained in recession in June, so the June quarter result was not yet the beginning of region-wide recovery. It was not until the December quarter that a true region-wide recovery was confirmed, when both Italy and Spain showed positive economic growth for two consecutive quarters for the first time since 2011.

Even so, with unemployment in Italy and Spain at an elevated level, and business and consumer confidence still supressed, it is important to put this result in context. It will take several more quarters of positive growth before firms and households have the confidence to spend and invest to the extent that unemployment begins to materially track downwards.

One place where unemployment has already begun to track down is in Europe’s third largest economy, the UK. The unemployment rate in the UK fell to 7.5% in the September quarter, having peaked at 8.2% two years earlier. In the December quarter, the UK economy grew by 2.8% from a year earlier, the fastest growth since March 2007.

With these signs having emerged that the UK and other major continental European economies are now in recovery mode, the remainder of this article takes stock of where these economies are at compared to their pre-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) levels. The article then concludes by commenting on Europe’s economic outlook. After all, the gradually strengthening recovery still faces downside risks, particularly stemming from structural reforms to banking and public finance, as well as the risk of disinflation in nations around the Mediterranean periphery.

Putting the recent recovery in perspective

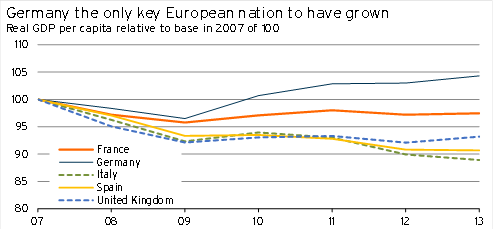

Despite Europe’s five largest economies all having entered recovery mode, it is only in Germany where GDP per capita has risen above its pre-GFC level. In other words, economic activity per citizen in France, the UK, Italy, and Spain remains below its 2007 peak (see Graph 5.26).

The economic recovery in Germany following the GFC began a lot earlier than its peers’ recoveries. The key contributors to Germany’s resilience were significant public investment by the German government and elevated export levels. German exporters benefited from massive demand from China following the implementation of the Chinese authorities’ stimulus package, as well as the depreciation of the euro.

Graph 5.26

Although economic conditions in the UK have improved significantly over the past year, the UK economy was one of the hardest hit immediately following the onset of the GFC. A key contributor to this decline was the UK finance industry, which is not only the nation’s biggest exporter, but also a provider of well-paid jobs. London is by far the world’s most important centre for over-the-counter derivatives, markets which froze during the credit crunch after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, so it is hardly surprising that the UK finance industry suffered significantly. The construction sector was also disproportionately affected by the recession, as unemployment rose and confidence to spend and invest waned.

Even with Britain’s financial services sector once again firmly in expansionary mode, and lower interest rates and improving job market prospects supporting the property market, economic conditions in the UK remain suppressed compared to their pre-GFC level. UK GDP per capita has to climb more than 7% before it returns to its 2007 level.

Italy and Spain have gone through a two-pronged recession. The first stage hit in 2008 following the GFC, and the second stage came to a head in 2011 as markets began to worry about the sustainability of government finances in these two nations. Even though signs emerged during the second half of 2013 that these two economies are stabilising, economic activity per citizen remains extremely subdued. Since 2007, GDP per capita in Italy and Spain has fallen by around 10%.

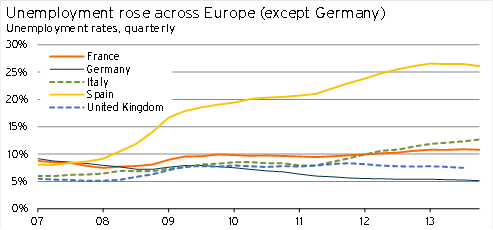

The decline in GDP per capita in the UK, France, Italy, and Spain since the GFC has also been mirrored in these nations’ labour markets. Graph 5.27 shows that unemployment rates in these nations have risen since 2007, with only the UK showing recent signs of improvements to its labour market. On the other hand, Germany’s labour market has strengthened significantly as part of its growing economy and is now in record shape.

The wild swing in Spain’s unemployment rate highlights the pitfalls of Spain’s two-tiered labour market. Around two thirds of Spanish workers have iron-clad permanent contracts, while the remaining third are on short-term contracts with little rights. At any hint of a slowdown, Spanish employers shed short-term employees due to the ease with which they can be removed. This situation was exacerbated during the recession by unions who continued to demand pay increases for permanent employees, forcing employers to make massive cut-backs to temporary employee numbers, thereby leading to a massive lift in unemployment.

Graph 5.27

The outlook for Europe

The recent improving economic trends in Europe are expected to continue over the next couple of years. We anticipate that economic activity in the UK will keep strengthening, rising by 2.7% in 2014 and 2.1% in 2015, while Germany will grow by a moderate 1.8%pa and 1.9%pa respectively. The French economy is likely to muddle along, growing by around 0.9%pa in 2014 and 1.2%pa in 2015.

Our central view for Italy and Spain is for the economic recovery that began in the second half of 2013 to continue into 2014. Although we are only forecasting economic growth in Italy and Spain of 0.5%pa and 0.8%pa respectively in 2014, growth rates should double in 2015 as the recovery becomes more entrenched. Even amid this pick-up, neither nation is likely to see real GDP per capita to recover to above its pre-GFC over the medium-term.

Europe’s economic outlook is not without its risks. The European Central Bank is of the view that persistently high unemployment in many euro-zone nations, as well as relatively tight credit conditions and falling inflation, are harming the region’s economic recovery. As a result, the ECB will keep target interest rates low and would not hesitate to intervene further to ensure that credit availability in embattled euro-zone nations improves and inflation does not fall further. Even though there may be some pricing pressure in Germany due to rising wage growth, the ECB would rather allow these pressures to persist than risk the fragile economic recovery around the Mediterranean wavering off course.

The implementation of the first phase of Europe’s banking union this year also poses risks to the euro-zone’s economic recovery. The first step of the banking union will involve the transfer of supervisory authority of most of Europe’s banking system from national authorities to the ECB. This process will necessitate assessing the financial soundness of banks, which could uncover some as-yet-unrecognised weaknesses that require capital injections or other intervention.

The European Parliament elections in May 2014 could also cause tension, as outside of Germany, there is a lot of dissatisfaction among citizens regarding current governance. European political institutions already have insufficient power to enforce accountability of national governments to European standards and election results could potentially further muddy the political landscape.

The issues that the ECB and European political institutions will continue to grapple with over the coming year are in stark contrast to the UK economy, where unemployment is falling rapidly, consumption is picking up, and the housing market is on the up. The Bank of England has previously signalled that it will keep target interest rates low until the recovery is ensured and the unemployment rate falls below the Bank’s 7% threshold. Given the way economic activity is picking up and employers are adding jobs, unemployment could fall below this threshold during the first half of 2014, suggesting that rate hikes could possibly occur by the European summer. However, the falling unemployment rate will also need to be accompanied by a lift in the participation rate before the Bank of England will be confident enough to start tightening monetary conditions.