Getting to grips with the changing composition of dairy demand

The massive spike in dairy prices during the 2013/14 season has simultaneously highlighted both the seemingly insatiable Chinese appetite for dairy products and a fundamental flaw in Fonterra’s milk price formula. This article expands these issues by looking at factors that will support Chinese dairy demand over the coming five years, as well as considering the likely supply response from other key dairy-producing nations.

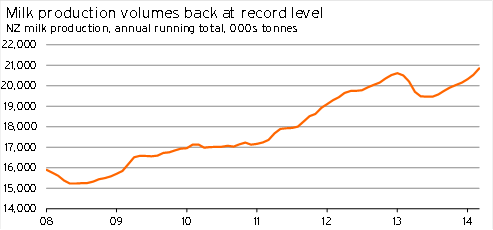

At face value, the dairy industry appeared to go from strength to strength over the 2013/14 season. Not only did soaring demand from China for milk powder propel farmgate milk prices to a record $8.40 per kilogram of milksolids (up from $5.80/kgms in 2012/13), but milk production recovered from last year’s drought and is once again at record levels. We expect total milk production to end the 2013/14 season around 10% above its 2012/13 level.

Graph 5.11

However, these buoyant headline numbers for dairy farmers have masked financial challenges for dairy product manufacturers – particularly Fonterra. These challenges arose because the formula that guides what Fonterra pays dairy farmers for raw milk rose much more sharply than the average output price the cooperative received across the diverse range of dairy products it manufactures. As a result, manufacturing margins were squeezed, and Fonterra’s normalised earnings before interest and taxation fell to $403m over the six months to January 2014 (down from $683m a year earlier).

A consequence of these plunging earnings has been a sharp drop in Fonterra’s full-year dividend forecast to 10c per share, down from 32c last year. Fonterra’s debt levels also rose by around $1bn, as less cash was floating around to meet working capital and investment needs.

Furthermore, things could have been even worse for Fonterra had the cooperative not overridden its milk price formula. In December, Fonterra announced that the formula was suggesting a payout of $9.35/kgms, but that the cooperative would exercise discretion and pay only $8.65/kgms.1 If such discretion had not been exercised, Fonterra would have incurred substantial losses and been forced to suspend dividends, or borrow even more heavily.

So what went wrong for Fonterra?

To understand what has undermined Fonterra’s manufacturing returns, we need to firstly examine what happened to dairy demand during the 2013/14 season and then show how the surge in demand fed into Fonterra’s milk price formula.

The value of New Zealand’s dairy exports rose by 31% over the March 2014 year, driven by an incredible 106% lift in exports to China. This additional Chinese demand accounted for 84% of the overall lift in New Zealand’s dairy exports during the year.

Graph 5.12

The majority of growth in dairy exports to China has been fuelled by rising sales of whole and skim milk powders. Sales of milk powders and products derived directly thereof accounted for close to 90% of all dairy exports to China over the year to March 2014. To put the sheer scale of China’s demand for milk powder in perspective, during the March 2014 year an incredible 34% of New Zealand’s total dairy exports by value were shipped to China as milk powder.

This surging Chinese demand for milk powder has contributed to a sharp lift in world prices for skim and whole milk powder. During the December 2013 year,2 the US dollar prices of skim and whole milk powder at Fonterra’s forward price auctions rose by 51% and 39% respectively over their average levels from the previous year. Although the prices of other dairy products also climbed, increases were more subdued than for milk powders. For example, cheddar prices increased by 30%, while casein prices rose 33%.

This sharp increase in prices for milk powders caused Fonterra’s farmgate milk price to surge as milk powders (along with their by-products) are the key reference commodities that explain changes in the milk price formula from season to season. The prices of commodities such as cheddar and casein are not incorporated into the milk price formula.

During the 2013/14 season, Fonterra has been processing as much milk as it could into higher returning milk powders. However, the composition of the cooperative’s current manufacturing capacity still means that around 25% of milk has to be processed into cheese, casein, and other products that are not reference commodities in the milk price formula. During the current season, these non-reference commodities earned negative returns, which pulled down Fonterra’s financial result.

To prevent this problem occurring again in future, Fonterra could either change its milk price formula to stop margins from being squeezed, or invest in additional milk drying capacity. Unfortunately, changing the milk price formula would be excruciatingly difficult, requiring complex negotiations between farmers and other stakeholders, not to mention government involvement given Fonterra’s position as a price setter of raw milk prices.

As a result, Fonterra’s preferred response to the dilemma has been to announce additional investment into milk powder production capacity. Fonterra will lift its capital expenditure by around $300m-400m over the next 3-4 years.

Although this strategy will give Fonterra more scope to avoid the production constraints that plagued the cooperative this financial year, the increasing focus on milk powder production concentrates risks on manufacturing margins from a single commodity group. With Chinese demand being the driver of milk powder returns at present, it is important to get a handle on the outlook for Chinese dairy demand.

Chinese rebalancing to drive dairy demand

The incredible demand from China for New Zealand’s dairy products over the past year is consistent with the story of Chinese rebalancing that we have been tracking in recent years. Rebalancing means that the Chinese government is promoting policies that push up consumption’s share of economic activity, instead of overly relying on investment and export-led economic growth. A consumption-led growth framework boosts demand for many of the food items that New Zealand exports, like dairy products.

Furthermore, as part of the rebalancing process, the Chinese government is taking a more active role in environmental protection. These measures are constraining China’s ability to grow domestic supply by restricting the quantity of available land and water resources for dairy and other agricultural purposes. As a result, China is being left with a shortfall in its ability to meet dairy demand and needs to fill this void by importing from nations such as New Zealand.

Official confirmation of this story filtered out earlier this year, with Chinese officials making unprecedented disclosures in public presentations in New Zealand. For example, in a speech at the Beehive, China's Deputy Head of the Central Rural Work Leading Group, Chen Xiwen, explained that China planned to retire sick land that was poisoned and focus its remaining capacity on providing staples such as wheat and rice. He went on to add that China was seeking international cooperation from foreign partners to meet growing demand for proteins such as dairy products and meat.

What is happening in China is a fundamental policy shift so, by design, has a long-term focus. Our central view is that Chinese rebalancing will continue to push up demand for dairy products over the next five years and beyond.

Although New Zealand stands in good stead to benefit from this uplift, other dairy-producing nations will also try and capture some of the bonanza. The following section considers the current and likely future supply response from some of these other dairy producing nations.

European and US dairy production is rising

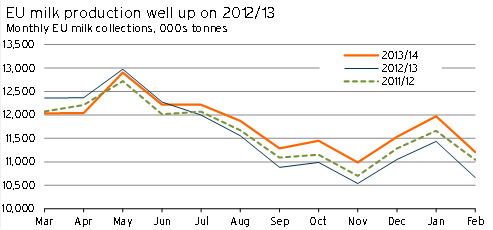

It is becoming increasingly clear that Northern Hemisphere dairy producers have invested heavily in increasing their milk production capacity in response to surging Chinese demand and elevated world dairy prices. Milk collections in the European Union over the three months to February soared 4.7% from a year earlier, while production in the US grew more modestly, up 1.0% in the March 2014 quarter from a year earlier.

Graph 5.13

The majority of milk in the EU and US is consumed domestically, but given the sheer size of the EU and US dairy industries, even relatively modest increases to milk production can massively affect the quantity of milk available for international trade. To put things in perspective, annual milk production in the EU is about 6.5 times New Zealand’s total production, while in the US the figure is 4.5 times.

Data from Eurostat shows that dairy exports from Europe are booming, with the volume of butter and whole milk powder exports rising 22% in January and February from a year earlier, while skim milk powder exports soared 49% over the same period. Although Russia remains the biggest buyer of European dairy products, sales to China are rising rapidly.

The volume of US dairy exports is also climbing, rising 24% in the March quarter from a year earlier. This growth was driven by strong demand from Mexico, China, and Southeast Asia.

With booming dairy exports from Europe and the US pushing up the global supply of traded dairy products, prices have eased substantially over recent months. Since peaking in February this year, average world dairy prices at Fonterra’s forward auctions have fallen by 25%. We expect further growth in dairy exports from Europe and the US to keep dairy prices subdued this year. In light of these trends, Fonterra has recently announced an opening farmgate milk price forecast for the 2014/15 season of $7.00/kgms.

The potential for increases in Australia’s milk production also can’t be ruled out. Although milk production in Australia over the March 2014 year was down 2.7% from a year earlier, production in recent months has begun to pick up. Furthermore, given that annual production levels in Australia are around 4.4% below their September 2012 year peak, there is significant scope for the Australian dairy industry to expand in response to expectations of sustained Chinese demand. The potential for competition from Australia is discussed in more detail in Agricultural competition from Australia? (p35).

China is actively diversifying its dairy supply chain

The increase in production from other dairy-producing nations is not only a result of producers responding to price signals, but it also appears that Chinese authorities are beginning to make an explicit effort to diversify some of China’s dairy purchasing away from New Zealand. This policy initiative is likely to remain a challenge for dairy farmers over the next five years and beyond.

China does not want to be solely reliant on the New Zealand dairy industry, as a drought, contamination scare, or sudden disease outbreak could leave China with a large supply deficit. Furthermore, the xenophobic backlash in New Zealand following the Shanghai-based Pengxin Group’s proposed purchase of the Crafer farms may also have contribute to this shift.

Evidence of China’s attempts to diversify its dairy supply chain is already emerging. For example, there have been some significant direct investments by Chinese groups into dairy manufacturing in parts of Europe, as well as the signing of long-term supply deals with existing European producers. The majority of these deals have focused on securing supplies of milk and whey powder.

Another example of China’s angst regarding supply security has been the recent implementation of a rigorous certification process for producers of infant formula. Most large New Zealand dairy exporters have gained certification, but several of our smaller infant formula exporters have currently been left without the right to export to China.

But there are some mitigating factors

Although these efforts by Chinese authorities to diversify their nation’s dairy supply chain will continue to challenge New Zealand dairy farmers, there are at least a few mitigating factors.

China’s diversification attempts do not mean that China won’t purchase any dairy products from New Zealand. The shift will simply mean that New Zealand can’t bank on continuing to capture such a high share of the Chinese dairy market.

This though is not so scary when one considers that China is not the only emerging nation with rapidly growing dairy demand. At present, dairy exporters have focused on the Chinese market due to a higher marginal return, but exporters could quickly redirect their supply to other nations in parts of South East Asia, the Middle East, or Latin America if this return premium narrowed. Bear in mind that although China accounted for 38% of dairy export receipts in the March 2014 year, China’s share was only 7.5% five years ago.

Furthermore, the dairy sector has a history of rapidly redefining its focus as it chases the highest marginal return. In 2008, for example, Venezuela rose from nowhere to become New Zealand’s most important dairy export partner, before disappearing outside the top 20 in late 2012, only to suddenly remerge in late 2013 to become our second-biggest dairy export partner once more. There is no reason to believe that the dairy industry won’t continue to display this kind of flexibility in future.

1 By May, these forecasts had been revised to $8.95/kgms and $8.40/kgms respectively.

2 December has been used as the reference period for comparing against export receipts to March. The reason for using prices from three months earlier is that information from Fonterra’s Milk Price Statement shows that prices are contracted on average 90 days (three months) before delivery.