Immigration policy is flying blind

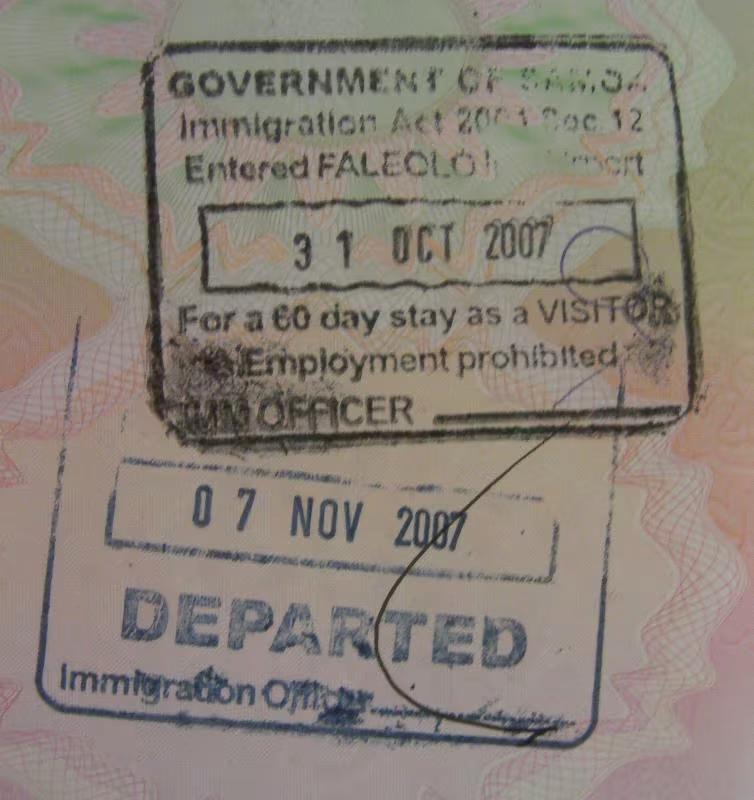

Last week the Government announced that from 3 October registrations for the Samoan Quota will reopen and from 5 October registrations for the Pacific Access Category (PAC) will reopen. These pathways will provide for up to 5,900 people to become residents over the next two years, which the government say will help reduce the impact of global labour shortages and help grow our economy. But will it?

More migrants…

Despite taking a harder stance on immigration than its predecessor, the current Government is taking steps to encourage more migrants to live in New Zealand. In the same week that the announcements were made about the PAC and Samoan Quota, the Government was patting itself on the back for reaching the halfway point for approvals of the 2021 Resident Visa. Over 100,000 new Kiwis can now call New Zealand home.

… to help stem the net outflow…

Some 5,900 new residents from Pacific Island countries over the next two years will help plug the hole created by the net outflow of migrants that New Zealand is currently experiencing – and is expected to continue experiencing for another 12 months at least.

The year to September 2021 saw a net outflow of 10,700 migrants from New Zealand. In the year to September 2022, we expect a net 9,000 migrants to leave our shores and in the year to September 2023 we expect a further net outflow of 7,800 migrants. That’s a total net outflow of just over 27,500 migrants. By the end of 2023 we expect net migration to turn positive again.

Stats NZ data shows that net outflows of migrants are currently being driven by non-New Zealand citizens, with arrivals of foreign migrants still considerably lower than pre-pandemic, but foreign departures back to more usual levels. Presumably these are people who were planning to leave New Zealand anyway but have been prevented from doing so in the past two years by closed borders. So too for those New Zealanders who are leaving, including young Kiwis who have had to postpone their Overseas Experience and older New Zealanders who are leaving on a more permanent basis.

…and help ameliorate skill shortages…

This net outflow of migrants, many of whom will have been participating in the labour market, has left the New Zealand labour market in dire straits. Reports of skill shortages are the highest they have ever been since shortages began to be measured in the 1970’s. According to NZIER’s Quarterly Survey of Business Opinion, in the June 2022 quarter a net 70% of firms said skilled labour was harder to find, and a net 69% said unskilled labour was harder to find.

Against the backdrop of 27,500 net outflows over the three years to September 2023, an influx of 5,900 migrants from Pacific Island nations over the next two years is significant. That’s assuming their visas are processed in time and the successful applicants are able to move to New Zealand. There are some indications of labour shortages in some Pacific Island nations which may place pressure on prospective migrants to stay.

But will these migrants have an appreciable effect on the availability of skills in the New Zealand labour market? Increasing the talent pool is more than just a numbers game. Migrants need to have the skills that employers are looking for.

…if migrants have the skills employers need…

We don’t know what skills and capabilities these migrants have. We can’t even look retrospectively at the types of jobs people in these visa categories went into in previous years. Unlike say, Essential Skills visas, the PAC and Samoan Quota visas have no occupation requirement and therefore no occupation data attached to them. It is probably possible to use the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) to track migrants who entered New Zealand on these visas in previous years to see what industries they subsequently worked in. But extracting IDI data takes time. So, for the time being we have to look elsewhere.

We do have demographic information. Looking at people who were approved for PAC and Samoan Quota visas between 2009 and 2021, they tend to be young people: 45% were aged between 0 and 19 years, 19% were aged between 20 and 29 years, 36% were aged 30 or more years.

Assuming the age profile of the 5,900 who are expected to enter New Zealand in the next two years is similar to what it has been in the past, that means just over 3,200 will be aged 20 or more years. We would expect many of these to participate in the labour market. Obviously, some of those who are younger than 20 years will also participate in work but we wouldn’t consider them prime working age because their skills are still developing.

Focussing in on those younger people. Based on past experience we might expect just over 1,100 of these Pacific Island migrants to be aged 20 to 29 years. This influx will help offset the net 7,100 20-to-29-year-olds who left New Zealand in the year to May 2022.

We might also consider the make-up of Pacific Island economies to get a sense of what skills these migrants will bring to New Zealand and therefore which industries will benefit from an influx of skills.

Between 2009 and 2019, around two thirds of people approved to enter New Zealand under the PAC and Samoan Quota visas were from Samoa, just under one-fifth were from Tonga.

In June 2022, around one-quarter (26%) of people employed in Samoa worked in public administration and a further 11% worked in commerce. Other key industries include transport (7.5%), personal services (6.0%) and financial services (5.2%) Tonga is a more agricultural economy with 20% of the workforce employed in agriculture, forestry and fishing in 2018 and 20% employed in manufacturing, many of whom were presumably processing agricultural products. Other key industries include admin and support services (9.0%) and construction (8.6%).

Without wanting to pigeon-hole these new migrants, if past is prologue, many will mainly be employable in the public administration, commerce, agriculture, and food processing sectors, and to a lesser extent transport, personal services, and financial services.

… and choose to live where their skills are needed

We also need to consider where these new residents might live. In 2018, almost two-thirds (64%) of Pacific Peoples lived in Auckland. Migrants tend to live where other migrants from the same communities live. It makes sense to live close to family members and other people in your social network, especially when you are new to a country.

In Auckland, the public administration sector makes up 3.9% of employment, small by New Zealand standards. Nationally, the sector makes up 5.3% of employment. Only 0.9% of the Auckland workforce is employed in agriculture and the food processing sector is small, making up 2.2% of employment. Although, the concentration of Pacific People in South Auckland is likely to be in areas such as Franklin/Pukekohe that do have more agriculture. Transport makes up 2.6% of employment. So, opportunities for people with an public administration, food processing and transport backgrounds might be thin on the ground.

In Auckland, 10.2% of the workforce is employed in construction so there may be more opportunities for migrants with experience in this sector. However, we are expecting activity in the Auckland construction sector to fall away in the next few years (albeit from high levels), especially in residential construction.

Agriculture-based economies such as Hawke’s Bay saw harvest volumes fall this year as workforce shortages left fruit rotting on the trees. On the face of it, an influx of workers with experience working in agriculture will certainly help growers. But, in 2018 only 2% of Pacific Peoples living in New Zealand lived in Hawke’s Bay, 1% in Tairawhiti, and 2% in Bay of Plenty. Recognised Seasonal Employer visa holders can be encouraged to work in New Zealand’s agricultural regions for the duration of the harvesting seasons. But can new residents from the Pacific Islands be tempted away from their families and communities in Auckland?

This examination is very back-of-the envelope analysis. People move between jobs that are in different sectors all the time so these migrants may be more employable than we are suggesting. On the other hand, many of these migrants will have limited experience working in New Zealand, which could make them less immediately employable.

Flying blind

To be fair, a lot of the analysis in this article is conjecture. But, in a sense, that is the key point. We don’t know what skills the people leaving New Zealand are taking with them. We don’t really know what skills employers are short of. We don’t know what skills a lot of migrants entering the New Zealand have, and whether they are the skills New Zealand needs. The Green List is designed specifically to help address skill shortages through immigration but it is not based on any quantitative understanding of skill needs and only applies to specific work visas. Policies such as the Labour Market Test are designed to ensure that migrants do not fill jobs that domestic workers could be doing.

Meeting skill needs is only one objective of immigration policy. We have humanitarian goals, for example. But as far as the labour market is concerned, for the most part, we are flying blind when it comes to setting immigration policy.