Finding workers to build Dunedin’s hospital

Dunedin is finally getting a new hospital, much to the relief of locals!

Current estimates put the cost of the new hospital at $1.4bn, with construction scheduled to take place over a six-year period from August 2020 to mid-2026. It will be the largest project in the area in living memory and will require different approaches to get the right mix of workers. In this article we draw on our construction sector and local labour market insights to examine the opportunities and challenges in store for Dunedin.

Looking back at other major projects

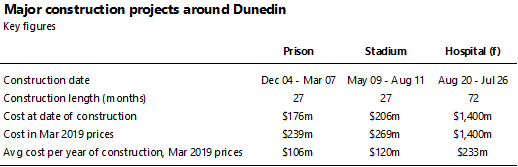

The two highest-profile construction projects around Dunedin over the last 15 years have been the Otago Corrections Facility at Milton (in the Clutha District) and Dunedin’s Forsyth Barr Stadium. Tables 1 provides key figures for these projects, alongside those for the proposed new hospital, showing just how large the hospital build will be.

Table 1

Apart from the fact that construction for Dunedin’s new hospital is expected to last almost three times as long as the other projects, the implied amount of construction activity per year for the hospital is roughly double the magnitude for either the prison or stadium. Even recognising the typical S-shaped profile1 of activity during a construction project (rather than the unrealistic assumption that an equal proportion of the project’s activity takes place each year), this result implies that the peak workforce required for the hospital development will also be double the workforce required for either the prison or the stadium.

Building during a boom or a bust?

The size and timeline of construction for the Otago Corrections Facility and Forsyth Barr Stadium were very similar. Both projects represented an increase across the combined Dunedin and Clutha area of about 50% in non-residential activity from the construction levels that prevailed prior to the developments getting underway. Both projects clearly created extraordinary demand pressures on labour and skills capacity in Dunedin’s construction industry.

However, a key difference between the two projects is the prevailing macroeconomic environment when they were built. Graph 1 shows that the volume of activity across various regional and nationwide measures of construction at the peak of the prison project during 2006 was 10-26% higher than it had been prior to the prison build getting underway. In contrast, at the peak of the stadium’s construction during 2010, the same volume measures were 11-19% lower than before the development had started.

Essentially, the prison construction came at the same time as a nationwide non-residential building boom, residential construction at historically high levels, and significant growth in infrastructure investment.

Graph 1

In the case of Forsyth Barr Stadium, overall local and national construction activity was 11-19% lower at the peak of the stadium project compared to the start. Based on our current view of the overall construction sector over the next 5-6 years, we expect Dunedin’s hospital build to coincide with a softer construction market and more like conditions during the Forsyth Barr Stadium build.

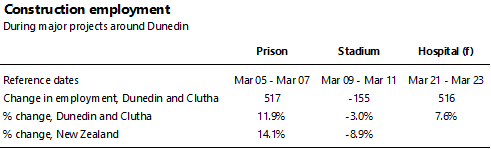

Any large-scale construction project will have implications for a small to medium-sized labour market, particularly during times of higher or lower construction activity. Higher activity higher competition for labour, with lower activity often resulting in it being easier to source workers. In Table 2, we see total employment in the construction industry in Dunedin and Clutha increasing 12% over the two years to March 2007 as the prison was built, although still lagging nationwide construction employment growth.2

Table 2

Forsyth Barr Stadium was built in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Both residential and non-residential construction rates were plunging, and even infrastructure spending was declining despite the government’s best efforts to stimulate activity. During the two years to March 2011, total construction employment in Dunedin and Clutha fell despite the stadium’s construction. Nevertheless, the drop was smaller than the 8.9% fall in nationwide construction employment.

Taking advantage of resources from elsewhere

In our view, the outlook for nationwide construction activity during the Dunedin Hospital build looks more like 2009-2011 than the 2005-2007 period. We are not forecasting a repeat of the GFC. However, residential consent numbers are unlikely to stay at their current 44-year high and the vulnerability of residential activity, particularly in Queenstown-Lakes, could free up capacity in the industry relatively close to Dunedin. We also expect nationwide non-residential construction to peak within the next year, given slowing economic growth and weak private sector investment intentions.

This softer outlook makes Dunedin’s challenge of obtaining the necessary labour and skills to complete the hospital build easier, because spare capacity in the industry is likely to become available in Auckland and Canterbury. With the right incentives, workers from these regions could be brought to Otago to support the resources already present in Dunedin and the wider region.

However, that’s not to say that finding all the workers for the hospital build will be easy – the scale of construction should still not be underestimated. Overall, the total number of workers required from either within Dunedin or other parts of the country during the building phase will represent more than 1% of Dunedin’s current population. Accommodating that many more people can have a significant effect on an area’s housing market – just ask Christchurch or Kaikōura.

And if you’re thinking of trying to get a smaller construction project done in Dunedin, perhaps you should do it now before the hospital build gets underway. For six years from mid-2020, tradespeople in Dunedin won’t be answering their phones for the small stuff because they’ll have bigger contracts to focus on.

1 Projects are often slow to start, ramp up with activity during the middle part of project delivery, and slow down towards the end when there are only loose ends that need to be tied up.

2 These estimates of employment are based on data from the Linked Employer-Employee Database, and location is based on the employers’ main site location. Employees working for a business from outside the local area can sometimes be coded to their “usual” location of work because the business does not have a permanent site where the work is being undertaken. As a result, our estimates might understate the employment effect associated with specific one-off projects.

Gareth Kiernan

Gareth Kiernan